Trapped behind the curtain

Uneasy with the intolerance toward my sexual orientation, I lay low. It took me years to finally break free.

I first heard my folks talking about freedom in 1990. It was not the twisted freedom of patriotic poetry or that of the uncertain past revered in history textbooks. It was our freedom and that made it real. For freedom, my dad left in the middle of the night to go to University Square and came home two days later, his face pale and eyes filled with tears. It was freedom that made my mom hug strangers on the street and shout out: “Ceaușescu has fled!” On TV, some people looked scared and claimed we wouldn’t know what to do with all that newfound freedom. But for a while, my folks leaped with joy.

My life, too, was in transition. I was 11 and felt I was starting to leave childhood behind. Suddenly I was among the tallest boys in my class, my arms had become upsettingly long and I didn’t know what to do with them. A dark shadow had grown above my upper lip, my face was blotched with painful craters, and my voice would break in incontrollable dissonances. Even more unsettling transitions were going on inside me, as I found the same exterior clues when studying the appearance of boys my age and that stirred in me emotions and feelings I couldn’t understand. I had started looking at them differently; I was fascinated by their agility and stubbornness, their outright determination to impress girls. I longed for a friend, but the admiration hidden behind this longing – which I considered unnatural – made me distance myself from them and get closer to girls. I didn’t have to hide my affection when I was with the neighborhood girls: we’d sing together, make up wacky games and, occasionally, I’d listen to their little confessions. I understood perfectly that Radu had the most beautiful blue eyes, that Tudor had a sweet laugh and Vlad was intelligent and sensitive.

But when alone, I tried to analyze my strange traits. I wondered why my behavior was different from that of other boys. Were others seeing these insinuating differences, too? They must have, otherwise they wouldn’t have called me a “sissy” because I played with girls and was scared of football. Then, in the schoolyard, I found out what “homosexual” meant, along with its entire name-calling spectrum. I understood from my classmates’ conversations that nothing was more revolting and disgusting than sex between two men. Homosexuals were sick degenerates with nothing but sex on their minds. Although I didn’t really see the connection between how I felt and the sexual act described by the kids my age in vulgar terms, I did have, for the first time, a possible explanation. If there was a word to describe such people, that meant I wasn’t alone.

My parents almost never touched on the subject. It was one of those so-called obscene things you don’t talk to your parents about and I didn’t know how to trigger such a conversation. If by chance the subject was brought about by a movie or in some random conversation, they’d just say:

“Oh, so he’s one of those.”

“Of what?” I tried pushing the envelope but my question seemed to upset them.

“You know, one of those, I don’t know why you’re asking such questions.”

When I was about 12, my dad gave me a hardcover edition of the Greek Mythology Legends. There were pictures at the end of the book representing ancient gods, including one of Apollo with a perfect body, completely naked. I circled Apollo’s crotch with a pencil and went to my dad so we could read together. When we got to that page dad remained speechless for a few seconds and then closed the book. He then gave me a whole righteous speech about the importance of books and I realized I had made a mistake. He asked me a few dozen times “Why did you do that?” but no matter how much I wanted to explain myself, I was afraid of his menacing eyes and couldn’t find my words. A whole bunch of words kept stupidly ringing in my head. Homosexual. Faggot. Pansy. Fairy. Why did I ever imagine any explanation could have come from him?

Every now and then I would try to get close to some boy my age. I’d forget all about my girl friends in the neighborhood, I’d go over to my new friend’s house and we’d listen to tapes, do our homework together or draw the most powerful robot. Sometimes I’d even gather up enough guts to get close to the football. I thought my dad would be proud of me and everything was fine for a while.

But I wasn’t the only one getting curious about the mysteries of sex; my friends had their curiosities and instincts, too: Bogdan wanted us to watch his father’s porn videos, Nicu wanted us to measure our trouser snakes, and Vlad would tell me in obscene detail what he’d do to Maria if she’d let him touch her as he wished. All this sex talk made me feel uncomfortable. I felt provoked in a strange way and I’d return to the girls, who welcomed me back cheerfully, no questions asked. With them, I could still be a kid. I was their old friend and they didn’t seem to suspect anything.

The signs were, by now, too many and I risked exposure: I hated football, I had too many girl friends, I was a dreamer and maybe a bit over-sensitive. I feared that even my good grades could give me away. I spent a lot of time checking myself in the mirror, making sure nothing showed. I had flat feet and I had to wear glasses, too. But it felt as if this was just the beginning. I would study my moves and my walk, I’d be careful to sit just in certain positions. I did all that without analyzing the reason behind my new obsession. It was just something that was part of me, a facet of my personality that I never had to show to anyone, under any circumstances. Although I wasn’t exactly sure what I was trying to hide, I was ever more convinced that my weirdness, if I was ever going to figure it out, would explain things that I otherwise couldn’t understand. Dad always seemed unhappy with the life he led with us, and mom would shed tears when she hugged me. They fought all the time – either for reasons I didn’t know, or because of me. Then dad left for Italy. Over the past years we had been strangers living in the same apartment, so the new arrangement was a relief.

During the last two years of middle school my hidden desires turned into sexual fantasies I considered shameful. Filled with remorse, I tried to understand how powerful these desires were. Were they something I had invented out of boredom? Was my imagination too wild? I wondered if there was some chance that I was a homosexual just because I had heard people talking about it. I used to do a quick test at the bus stop. I would seek out what was generally considered a beautiful person, man or woman, and ask myself: “What am I feeling now?” I was trying to identify my sexual impulses and would ask myself quickly, leaving no room for hesitation: “Am I really a fag?”

The perfect case was when I’d lay eyes on a couple of lovebirds because that’s when I had the possibility of direct comparison. “Which one do I like best? What’s sexier: her legs or his arms?” As it were, I had to deny myself an answer many times. What was, in the end, the difference between beauty and sensuality? What was I supposed to be looking for? I would tell myself: “They’re both cute and seem to be getting along just fine.” But other times I’d be taken aback by the way his lips twined when he spoke; his movements seemed so firm and precise and it was so easy for that boy at the bus stop to have the world wrapped around his finger. Upset, I’d go back home, and promise to do better on the quick test the next time.

In 1993, I started high school. It was around that same time my parents decided the only way to save their marriage was for mom to go to Italy, too. I was left home with my grandma. The fact that no one knew about my inner turmoil made me feel lonelier than I already was. Stunned, I realized I had the freedom every kid my age longed for, but no idea what to do with it. I got closer to two old friends in my neighborhood, attracted by their rebellious spirit. I wanted to rebel, to be able to say something out loud. She was the first girl I ever kissed and he was the first boy I fell completely in love with. We spent those summer evenings at her place (her folks left town a lot) or in parks, listening to The Doors and getting drunk on cheap booze. “Come on baby light my fire”, Jim Morrison sang. An erotic movie from the ‘70s was on TV, complimenting the music, while he was playing around with the bulge in his pants, shooting aroused glances at her, then at me. The cloud of alcohol hanging over our minds made everything seem possible. I tried to tell them. “There’s something wrong with me and I want you to know it.” As soon as I heard the sound of my own voice, I regretted it. I remembered all the bullying in the schoolyard and got scared. Just a few days before, we had been discussing Jim’s loathing of homosexuals. They looked at me all wide-eyed and I had to lie to them. “I think I like drinking a little too much.” We all laughed.

The next night, we’d had too much to drink again, and I was lying face down on the couch, drenched in cold sweat and shivering. He lay on top of me, gripped me in his arms, then held my face between his hands. “If you’re a fag, I’m going to kill you with my bare hands, put you out of your misery. That’s a promise.” The weight of his body and his hot lips pressed against my ear had just confirmed it. I was a fag and I loved my misery. I wished he’d had his way with me, right then and there. The next day, I decided to give up my new friends, all the rebelliousness and the alcohol, but I kept Jim’s music.

The circles of friends from middle school and the neighborhood broke apart and a new challenge ensued: high school. I had learned from the past, I was more confident in my ability to play a role; I wanted to fit in at any cost, be a normal young man. I had taken all those uncomfortable things that adolescence had brought into my life and locked them in a secret closet, hoping they would eventually vanish. I started grasping the game behind social relationships, figuring out its rules and predicting behaviors. I used all this new information to build an image for myself: I was the smart guy, a bit secretive with his own thoughts, but ready to listen to friends’ troubles and offer a word of advice. I was the one in the middle of the dance floor at school dances, the one who’d burst out laughing at the theater startling the entire audience, the one who’d start singing loudly in the street. I was either calm and ironic, or eccentric and noisy, predicting what people around me wanted me to be.

Like any teenager, I’d gained a sense of pride and being humiliated for the feelings I had towards my fellow mates was a recurring nightmare. The cruel jokes from the schoolyard had turned into observations that took on a feigned tone of indifference. “I think your buddy’s gay,” a guy told one of my girl friends. We were at a party where, luckily, I didn’t know that many people. I caught his scornful smile. “Look at him, he’s a ladyboy.” I laughed as if amused as everyone stared at me. “You’re being mean,” my friend said, and that hurt me even more. I didn’t need protection; I needed a voice to firmly deny what had been said about me. “I’m not being mean at all. I’ve spent a year in the States and I’ve seen his kind. I’m telling you, he’s a fag.”

I left without saying a word.

Around tenth grade, my classmates were giving in to prodigious love stories, spoke passionately of consuming desires, and the group I was in was seeing its first relationships take shape and its first dramas unfold. I wanted an affair that would bring me in line with my friends, I wanted to spend the night talking on the phone, skipping school and having dates in the nearby park or at the coffee place across the road from my high school. Everyone else seemed to be fooled by my pretentious, witty boy attitude, alas convincing myself was not that easy a task. But I wasn’t about to give up – I was determined to prove to myself that I could do it. The determination to belong gave me the power to fight. Just as others had learned to write with their left hand, I would have to learn to love a woman.

I was 15 when she came back into my life. I’d known her since we were kids and played together in the little park outside my building. She had slightly almond-shaped eyes, a heart-shaped mouth, and probably the most beautiful breasts in the world. She read incredibly fast and memorized unimaginable quantities of information. In her summer dresses, I sometimes wondered whether she was a butterfly or a goddess. We decided to go to the seaside together and, after the timid attempts of the first days, on the fourth night we danced, drank wine, and then kissed – once, and then again. The next day I awoke with her in my arms and felt I could belong to her.

It was fine in the beginning. I had a beautiful, intelligent girlfriend, I was loved and that boosted to my confidence. The worst was behind me and I was thinking I would gradually come around. I loved her, and how could it have been different, for she was the solid proof of my normalicy? There was that sweet intimacy I had never had with anyone and the passionate sex that would put an end to spurs of teenage angst. Then there was her stubbornness to provoke me and the tenderness with which she sought my protection. Not least, she was my best friend and, except for my fascination and hidden sexual yearnings, she knew everything about me.

I felt good around my friends; I was finally one of them. Freed from the fear of being uncovered, I managed to build more lasting relationships with guys of my age. We went out together with our friends, we took road trips. Everywhere, the two of us were the eternal lovers, always holding hands, always with a kind word and a caress for the other. I wanted to give her all the affection she wanted: it was my way of saying thank you, as well as of chasing away the obsessions and torments that consumed me.

High school years went by and I went to college. My parents decided to split up but that was not unexpected: mom came back to the country while dad, whom I hadn’t seen in years, stayed in Rome. I saw my girlfriend every day and, even though we rarely spoke about them, our plans for the future were pretty much laid out and quite clear to us and everyone around. We were the high school sweethearts bound to get married a year or two after finishing college. She dreamed of the perfect wedding and the dream house. I wanted a beautiful daughter who would look like her and a son I would name after that boy with sensual lips, my first love. Just as I had wished when I was 14, I was now moving along a path that comfortably sealed my normalcy.

But when alone, I was disappointed to find my sexual orientation had not changed. The look, the voice, the body of a man – they could still stir something in me in a way she never could. I wasn’t blind, I understood how special her delicate beauty was and how sweet her tenderness, but my sexual desires took a different road. I would cry when alone and ask myself why I was unable to love her all the way. Why did those foul obsessions keep popping into my head, why did I imagine myself kissing a man, why did I long to see his naked body, to touch him? I would wipe away my tears and tell myself I needed to stop with this despair. There was a whole world waiting for me out there, and above all, there was her. Other times I’d play with the idea of a sexual affair with a man, although I had no clue where or how I could meet someone. It could have been a sure way to understand what I was up against, I remember thinking. But I couldn’t bear the thought for more than a few minutes: I could never do this to her, I would be a monster. I felt guilty for the crooked way in which I was trying to justify a potential surrender. I was weak.

After five years, I felt I couldn’t take it anymore and all that inner turmoil had to stop. We broke up for a few months, during which time I wanted to be the jealous ex-boyfriend, even though I wasn’t.

Loneliness was excruciating because I wasn’t ready to deal with my sexuality; my struggle intensified and was eating me up inside. I wasn’t going to confide in anyone – I was convinced that hiding was the best option. I had heard of men meeting up for sex in the park near the Opera House or in the public toilets below University Square. So that’s what being gay was all about – writing lewd messages on bathroom walls and screwing complete strangers in parks. That was not the fate I was willing to accept for myself. So I called her in the spur of a moment.

A few days later, we were at the seaside again. History repeated itself and we got back together. When we retuned, I dropped her off outside her building and rushed home. I locked myself in my room and picked up the phone. I was going to tell her it had all been a mistake. I never dialed the number. Instead, I listened to the phone beep for minutes on end.

Nothing was ever the same. I started playing my role mechanically. We’d see each other less because her mother didn’t approve of our relationship and she didn’t have the guts to stand up to her. Sex, too, was monotonous and occurred a lot less. I think she was beginning to understand too, not necessarily my sexual orientation, but the fact that her feelings weren’t reciprocated. Her suspicions had a layer she didn’t understand and that made her insecure, always seeking confirmation while I wondered uselessly why she was so mad. She wanted the certainty of a future and a family with me, while in my mind, I defended that I was giving her everything I could. I think I wasn’t paying attention to her suffering because I was too afraid of my own failure. It is so that we began the seventh year of our relationship.

I was 22 when the death of my grandmother on my mother’s side made me see the foolishness of the bet I had made with myself. When factored into the equation of life, death shifts perspectives. My grandmother had taken her own life and this severed all ties I would have with my mother for a long time; there was too much blame and too many reprimands on both sides. If I could, I would have erased all the past I knew.

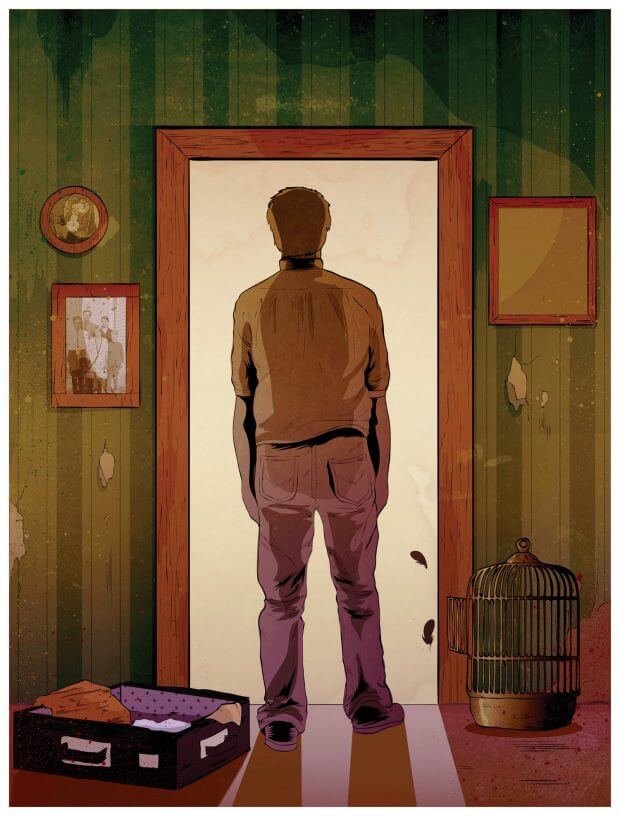

I moved out to live alone. I could have lived with my girlfriend but I was seeking solitude and cherished it; I wanted to escape my own life through a side door. I looked in the mirror and saw a stranger, I told myself I needed to break free and give myself a chance to be happy. The shadows of death had made me realize I wanted more from life than just being the winner of a game of deceit. For the first time, I realized how important it was to be where you wanted to be, with that certain someone you could feel at home with. With him, the one I hadn’t yet met, but whom I wanted to try and find.

Then I thought of my girlfriend, that girl who was once a child like me. Time wasn’t standing still for her either. Those seven wasted years of her life were now a huge burden on me. Our meetings had become painful: she was no longer my lover, she was my private casualty.

I never confessed anything to her and never asked for forgiveness. I only told her our relationship couldn’t go on anymore. Uncaring, I convinced myself this was the best for her: a quick break-up, no explanations. We met up for coffee a few months later. The conversation was strenuous amid uncertain looks and unuttered thoughts. We wore the masks of ex-lovers happily continuing on their own paths. We parted as if we were two friends who would meet again in a few days. We haven’t seen each other since. I wrote her a few lines a couple of years later, but I never sent them:

“I’ve forgotten the sparkle in your eyes when they met mine; I’ve forgotten how you used to cuddle with me and how I was your knight in shining armor. I’ve also forgotten the passion of our first night together and the ecstasy of those that followed. How familiar your voice sounded and how I longed to see your face. I’ve forgotten how I became a man. I don’t remember the sheer joy of unsaid words and tender touches. You’ve become a shadow cast in an emptied corner of my soul and I’ve forgotten you for fear of your memory. I’ve forgotten you and, most importantly, I forgot to say I’m sorry.”

You learn to live behind the curtain. People see you as deviant, though no certain diagnosis is offered: is it your soul or your mind? Is the anomaly hidden somewhere inside you, in your blood, your tissue, your bones – or is it all about social circumstance and the family environment you grew up in? When you’re hiding from those around you, you’re also hiding from yourself. You’re not a friend, you’re not a son, you’re not a colleague. You feel you’re just an illusion, a shadow of what you could have been had you been free to show yourself to the world.

In the winter of 2001 I was living alone in a studio flat and took the subway to work, to the headquarters of the insurance company where I started working after graduation. In the evening, I would go to the internet café around the corner from my building and log pnto #gaybucuresti, the chat room used at that time as the main communication channel by the gay community. I wouldn’t go on any dates at first; I was just joining in the conversation, hence being called a teaser. But in reality, at just 22, I was scared of my lack of experience with men. During the chat room searches I’d swing from trying to find the love of my life, to a one-night stand, and thus found pretexts to avoid any date. Slowly I overcame my shyness and realized I was raising false issues. I did want to meet people like me. I’d go out at night with friends and sometime after midnight I’d get a message and excuse myself, saying I had to go on a date. Any questions were blocked by my dumb, mysterious pretence of a smile.

I can’t say I had friends in the gay community; perhaps a few acquaintances I saw now and then. Still, it was a step forward – now there were people who knew I was gay. In the six months since my first date the scenario repeated itself a few times: an interesting conversation in the chat room, a meeting with a guy over a coffee, then a more or less hot night together. Everything would be over, if not immediately, then within weeks. On some weekends I’d go to Queens, the only gay bar in Bucharest at the time. I told myself I was looking to hook up but what I really wanted was a friend to talk to about how I felt. I saw this as a weakness and worked even harder to convince myself that all I wanted to do was have sex with men. There was something simple in this, in taking your clothes off in front of a stranger, not caring whether you’d ever see him again. Sometimes I did it. The only thing that betrayed my nervousness was this shiver that took over my entire body. “Are you cold?” my one night-stand would ask me. “No, I’m fine. I like it.”

And it was sex I thought I was after that evening in July 2002 when I went to Queens. The scorching heat outside had mellowed and I had to get out of the house. We saw each other on the dance floor – we got closer, we started dancing to a funny song, laughing for no reason really, then we started touching, then kissing. I couldn’t take my eyes off of him, we both smiled and we didn’t even have to say anything. I did ask him his name. He was Alin and I seemed to be orbiting around him as everyone else seemed to be fading out of the picture. And he was dancing with me, kissing me, rubbing himself against my body. His eyes seemed to say a thousand words. Suddenly, this ease troubled me and I wanted to get out of the nauseating projection of the strobe globe above us. Before I went home, I gave him my number and invited him over the next day.

When he stepped down at the bus stop, he smiled shyly. We went home and ate, talked about music, and Queens, and the gay community in Bucharest. He told me that almost everyone around him knew he was gay. I felt I was leading a double life but I didn’t want to tell him that. Some things are better hidden in the beginning; I didn’t want to scare him away. I was thinking how to go about kissing him. Was it too soon? We talked some more, we lit a cigarette. The conversation was flowing and that made me want to touch him even more. I drew closer to him and ran my fingers through his hair. I kissed him. What I felt then – that tremor, that extraordinary vibration that shook both our bodies at once – that is the most precious memory I hold in my heart.

We couldn’t keep our hands off each other. Our bodies searched each other frantically. His friends always joked: “You guys are like suction cups.” We shared the same moments of joy and the same little worries. In our studio flat in Berceni we were lovers. When we stepped out of the building, we became roommates. We got on the subway and turned into good buddies until we got to a friend’s house. There, we were allowed to be a couple again. We had to abide by these rules and hide a part of what we genuinely felt.

Sometimes we’d slip up. We’d meet in town after work and I’d forget I was supposed to hold out my hand and would find myself almost kissing him. At the restaurant, he would hold out his fork for me to taste the food. I’d call him Baby without realizing it and he would sometimes gaze into my eyes for too long. One time, we stopped by a grocer’s stand near the subway to buy tomatoes and started talking about how many we should get, then we started picking them.

“Let’s get the big, nice ones,” one of us said. “No, let’s get the smaller ones, they’re tastier,” the other chimed in. We had been living together for over three years and surely we must have been communicating like any other couple in such a situation. But the man was infuriated: how dared these fags touch his tomatoes?

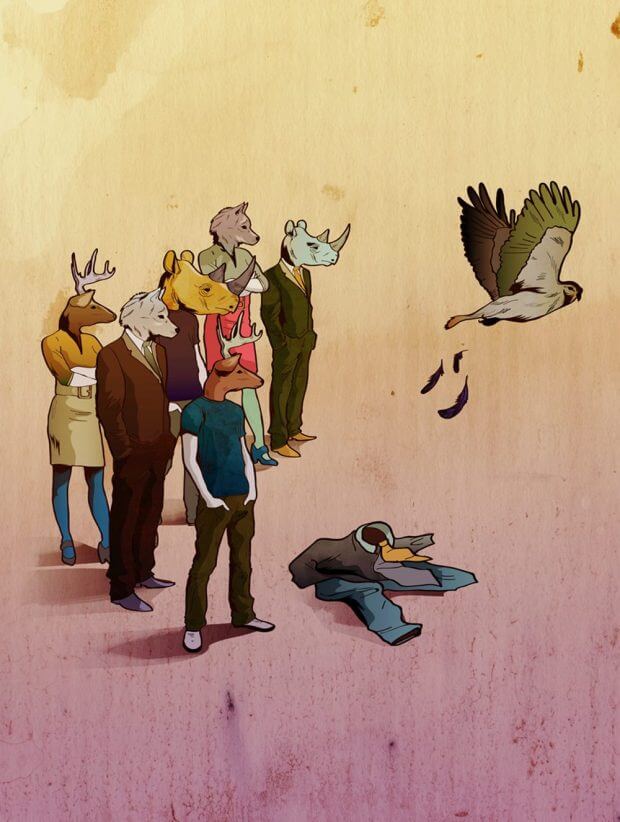

We wanted to come out to our parents, to the neighbors, to co-workers, to the rest of the world. We talked about this and admitted our fears to each other. This was a way of seeing things we had both grown up with; we felt this was what the majority expected of us, including our parents. To say you’re gay would be to disappoint, to cause repulsion, to inspire pity. You tell yourself the hatred is not directed at you personally, it’s too irrational. People speak about fags in general, they don’t know who we are. But the choir of voices keeps going every chance it gets and you can’t help but feel defeated. You lose the courage to be yourself and accept the standard of the majority as the only measuring scale. Their truth becomes your truth.

I finally told some close friends that I was gay. But I continued hiding from most of them because I didn’t want to be judged. All sorts of unlikely scenarios kept playing in my head: they would kick me out of their house; they would shake their heads and vanish from my life forever. For no real reason, I had decided they would not accept me, so I preferred to gradually lose touch with them. I thought it would be less painful that way and I found refuge in Alin’s circle of friends.

I had decided my family couldn’t possibly understand and I used lies against them. You don’t understand, well, then you’ll never know me. In fact, I had never even tried to explain anything to them. My grandmother on my father’s side was concerned. “Still alone, my dear boy? Why aren’t you seeing a girl?” With dad, things were easier because he was in Italy; we spoke rarely and I always managed to make up some story that left no room for questions. I saw my mom rarely and I wondered what was stopping me from trying to get closer to her: a death from the past or my present life?

Conversations with co-workers also avoided certain topics. My professional career was advancing rapidly but I was certain my sexual orientation would not be accepted at work. One of the firm partners ranted against the “damn Jews” every chance he got; I wasn’t keen on hearing what he had to say about homosexuals. At the same time, I enjoyed the company of many colleagues and considered them my friends. For some of them, I made up a mysterious girlfriend, probably married (that explained why we were never seen together), named Paula. It was complicated to tell people about my vacation plans with my roommate – our living together was already a clue I feared could give me away. Whenever we returned from a trip I’d spend half a day sorting through photos. There was always something that could give me away: in Maramureș we had been too close, and in Mamaia we were always wearing each other’s clothes.

I never went to the gay pride parade in Bucharest and neither did our few gay friends. There was something at stake for everyone but most of the time the reason was that they would disappoint their parents or would end up losing their jobs. We all migrated from one small circle to another, from one gay-friendly oasis to the next.

If you had asked me at that time what was stopping me from marching in the parade I would have said bluntly that I didn’t feel like having a bunch of idiots throwing tomatoes at me. I only went to gay-themed film screenings that were part of the festival and that was enough to make me feel like a hypocrite; I lacked the courage to be out and proud. On the weekend, we’d go to the only gay club in Bucharest, where we had met. It was the only option because we didn’t want to spend our evening some place where we would have to hide.

But in our small universe we were happy and I often thought, with that typical infatuation of someone in love, that what we had was unique and never ending. I would tell myself that life is an endurance test and love is what pushes you forward.

In the summer of 2005 we visited a friend who had moved to Brussels to study. The memory of the excitement we both felt simply because we could walk hand in hand on the street never fails to make me smile. We glanced at passers-by looking for the slightest glimpse of rejection, of judgment. We walked around in Brussels, we hugged on the banks of the Seine, we kissed in the middle of the square in downtown Amsterdam.

Once you’ve breathed in the fresh air of freedom, it’s hard to ever forget it. We got back to our studio flat in Berceni and started looking for a way to escape. We spent months making emigration plans. First it was Canada, then Australia. It was hard: we had no savings to start anew, emigration conditions were harsh, we needed to have our schooling recognized and that could have taken years. We were told it was very hard to find a job, that no one would give you the time of day, that you’d be forever a foreigner both there and in your own country. But nothing could stand in our way; we knew it was only a matter of time.

Some of our friends understood our new obsession. They’d say we’d never be able to live the way we wanted to in Romania, that our love deserved more. Others said we were out of our minds, that everything important was right there: our love, family and friends, a home and a decent living. None of us could imagine what lay at the end of these searches; all we knew was that we had to run away and that we’d be together at the end of the road.

There was no need to fill in emigration forms. I was telling a friend about my summer vacation in Belgium; that’s how I learnt that a financial consulting firm was hiring in Brussels. It all happened very fast. In the fall of 2006 I hugged my boyfriend, family and friends and hopped on a plane, and at the beginning of 2007, when Romania joined the EU, Alin joined me.

Since my grandmother’s death I had only seen my mother sporadically and every meeting ended with an argument. I had been in Brussels for a few days when she called me. I could hear her fading voice on the phone, muffled by tears. I paced back and forth through the apartment, angry with her for insisting on having this conversation over the phone, but mostly angry at my former neighbors in Berceni who had told her in great detail about the suspicious relationship her son had with a brown-haired boy that also lived there.

“Forgive me, but I need to know. I can’t live like this, not knowing for a fact,” my mom was saying. I sensed there was only one thing that would convince her, so I confessed just to put an end to her questions. “I’m happy. That should matter, right? Isn’t it enough that I’m happy?” Everything was silent for a few seconds, then mom said: “Please, don’t talk to me like that. Don’t mock me.”

I don’t know whether I was laughing or crying but my vision was blurry and my voice was stifled. “I’m happy, mom. I’m happy and that’s how I wake up and go to sleep. I look around me and can’t see anyone happier than me. I love him and I never imagined I could live something so beautiful.”

Alin was still in Romania as I was telling all this to my mom. I told her how I wandered the streets of Brussels with faltering steps, how that distance of over two thousand kilometers drowned my soul in sorrow, how I waited eagerly for evening to come so I could hear my boyfriend’s voice over the phone. Mom was comforting me and crying with me on the phone and, after all this time, I felt like I was her child again.

Since then, we’ve started talking more often. She’s even visited us twice. She’s always saying how beautiful we are together and how lucky we are to have found each other.

I told my father three years later. Being so far from each other for such a long time, it was hard for me to figure out a good time to confess. Occasions were rare and I asked myself what he would make out of that information. In 2009 I turned 30 and I decided I had to do it as soon as possible. I wrote him an e-mail and he replied the very next day. He was glad I was not alone and he loved me.

My grandmother now has a new grandson and my aunts and uncles have a new nephew. They always ask me to put him on the phone. They’re crazy about Alin, and I certainly can’t blame them.

Romania is today the place where my family and some of my friends are. As soon as I fully acknowledged that I was normal, I no longer allowed myself to hide from people, regardless of whether they were around me or a three-hour flight away. I tell everyone who I love, and today there is no fear and no shame in my life. My friends and co-workers in Romania have found out from our talks or at least seen it on Facebook. No one had bad things to say about it. A few contacted me seeking confirmation and I gave it to them. Distance makes things easier, but I tend to think their reactions wouldn’t have been much different had I stayed in Romania, close to them.

When I got to Belgium I decided I would tell people who I was from the very beginning. If you want to know me, then you must know I am gay. What I do in bed is of little importance. But what is really important is who and how I love because that is the biggest part of who I am.

For people here, my relationship with another man is not something out of the ordinary; my co-workers and I share anecdotes about couple life, and friends say they can only imagine the two of us together. I now realize it was me I had to convince first, not everyone else. I still wonder sometimes if I’d ever have managed to do this had I not left the country, if I’d have managed to build up enough courage to raise my voice, stand up to the opinion of a noisy but otherwise unknown majority.

Although I left Romania of my own accord, when I go back I feel as if I were banished. Maybe not so much by the people, but by my own thoughts, by a need for a level of self-acceptance I couldn’t have achieved in those circumstances. Our mind is a prisoner of those particularities that make up life’s immediate existence. Reading about free people doesn’t help you truly grasp what it’s like to live free.

In Belgium, I changed. I smile at people when I walk down the street. I don’t think it’s weird that the guy passing me by is humming a song; on the contrary, I listen to see if he’s got a nice voice. I sympathize with the lady in front of me who stops all of a sudden to look at the scenery. I’m no longer on the run either. I say “I love you” to Alin just as often but I also try to show it to him in different ways. I make more time to read and write. At 30, I learned to ride a bike.

Happiness is hard to put into words. This summer, it has been nine years since Alin and I first got together. We’re both changing and yet we’re still so close; sometimes I feel we’ve come to exist as different facets of the same being. In the morning, in bed, I hold him and the world wraps itself around us. Still drowsy with sleep I let myself slip into a sweet confusion – for a few seconds the line that separates my body from his fades. In the freedom of our embrace I find all the happiness that I need.

Acest articol apare și în:

S-ar putea să-ți mai placă:

Ce ne spun pietrele și zidurile despre istoria sclaviei

Un cercetător identifică „locurile memoriei”, adică locurile în care sclavia a lăsat urme la nivelul întregii societăți.

Zi-mi câți ani ai ca să știu cât trebuie să muncești

Sau ce înseamnă să fii milenial cu serviciu.

Cum ne-am învățat copiii să vorbească despre ei

Am folosit masa din bucătărie și metoda App Store ca să ne cunoaștem copiii.