The Ghosts of International Adoptions

Tens of thousands of abandoned children were adopted internationally between 1990 and 2004. Many of them are trying to understand their roots but their search can be overwhelming as the Romanian state still hasn’t recognized it has failed to protect them.

By Ana Maria Ciobanu

Photographs by Bogdan Dincă & Mike Carroll

Archival images courtesy of the Museum of Abandonment

Translated by Oana Gavrilă

23 december 2022

I’ve made a habit out of checking The never forgotten Romanian children Facebook group and other similar groups whose shared mission is to reconnect adopted children with their birth families. I read through the discussions of Romanians scattered all over the world, united in their desire to know about the lives they had before they joined the ranks of the more than 30,000 who left the country with their adoptive parents.

“Greetings from Canada”, “Hello from Italy”, “Hi from France” write young people aged between 20 and 40 who are seeking for their roots. They post photos from their childhood and current photos of themselves hoping some relative or some neighbor might recognize them. Many say they have been brought up by wonderful families and are grateful to have grown up abroad; but they’re missing their story at home.

They left Romania bearing the label of “Ceaușescu’s children”, a curse and a reason for estrangement. They were the product of the communist pro-natalist system that had controlled women’s reproductive lives and had filled state care institutions with unwanted children and too many mouths to feed at a time when heat was scarce and there was not enough food. When communism collapsed, Romania had the biggest rate of institutionalized children in Europe – 2.4% of all children under 16.

Some of the people in these Facebook groups know the names of their Romanian parents. Others remember they had siblings in the orphanage from where they were adopted. Most point out they don’t blame their biological families. “I’m not searching for you to pass judgment, I just want to know you,” writes a boy who says he was found in the stairwell of an apartment building and taken to an orphanage and his real identity could never be assessed.

Sometimes people get such long-awaited comments as: “I’m your sister, I’ve sent you a private message”, “You have 3 other sisters and one brother, I’m their neighbor!”, “Have you found your mother? My mother knows her!”.

Lucian Schepers had hoped for such a comment after he posted his story on the group page. “My name at birth was VOINEA LUCIAN IONUȚ. I was born in CONSTANȚA or BUCHAREST on 04.07.1986 or 21.07.1986, to this day I don’t know my date and place of birth for certain,” his post began.

When all you have at hand to understand who you are is a bunch of documents in a foreign language, confusion is inherent. Several commentators explained to him that his personal identification number shows he was born on 20 June 1986. But he also has passport issued in 1993, bearing the stamp of the Socialist Republic of Romania, where his date of birth is listed as 20 October. The issuance dates for these documents are also confusing. There are too many papers – some bearing his Romanian name, others his Belgian name – most of them issued the year he was adopted. He doesn’t know which to trust.

What is certain is that Lucian is 36 and he was adopted in 1993 by a Belgian couple.

Last year he sued his adoptive family to renounce their name. The Belgian court overruled his claim, saying that was not a right but an exception approved only by the king when it is of no harm to anyone. Going back to his Romanian name wouldn’t change the fact that the Schepers are legally his parents and would create confusion, the court explained and ordered him to pay over 1,000 euros in taxes for unnecessary claims. And so Lucian moved to Bucharest to try and understand on his own what happened in the first seven years of his life. He is convinced the documents he has received are false and he wants to prove it to restore his identity. That is the plan he keeps repeating to me since July 2022, when I met him.

Lucian is one of those people who cannot move on in life without knowing their full identity. They’ll try anything – lawyers, emails and phone calls to dozens of institutions in Romania, complaints to the police claiming to have been the victim of human trafficking, endless online searches. He wants to fill all the gaps left by his papers because there are years of his life he knows nothing about and not knowing keeps him up at night.

“There are gaps! It’s not normal to have no idea where you lived for two years! Wouldn’t that terrify you?” he asked when I explained that back then abandoned children would routinely spend two years in the hospital before authorities placed them into care. Lucian hopes that once he finds out the truth he will finally begin his life and forget the life he feels he didn’t choose and which only harmed him.

Studies analyzing the development of Romanian children adopted from institutions have shown a strong cultural identity helps stave off depression, self-harm and suicidal tendencies and contributes to the development of a healthy sense of self. When you’ve been told you were saved from a horrific place in a country that mistreated its children and you are constantly reminded that you’re different – the name you were given at birth, the color of your skin, your accent in your adoptive language –, it’s like you’re always floating between worlds without ever feeling like you belong anywhere. International adoption also leads to the construction of a dual identity. If as a child you haven’t felt that you truly belonged in your adoptive family and the new culture, finding yourself in your native country promises to fill a void but it can also swallow you whole.

I wanted to understand Lucian’s search because it is a tragic instance of an identity void shared by thousands of people with similar fates. Over the past five months I have stood beside him while he obsessively sought explanations for each tiny shred of information that could free him from an existence he describes akin to a CD that’s stuck on a loop, which he is forced to listen to over and over.

The group where I met Lucian is a microcosm of Romania’s past. In 1990 the country had over 100,000 abandoned children. Because the story we told ourselves was that these children had no one, that foreigners wanted to give them a family seemed an ideal solution. Romanians were struggling with poverty and didn’t generally adopt children who bore the stigma of orphanages. Foreigners wanted “Ceaușescu’s children”, as the international press had dubbed them.

Behind this label, however, were biological families that lacked the means to raise these children, there were teenage mothers who didn’t have access to contraception and dozens of years of propaganda portraying the state as a parent better fit to educate and bring them up in the spirit of communism. Some of the “orphans” had families that visited them or took them home on holidays. There were mothers told themselves they would take them back once their circumstances improved – once they had heating, running water and enough food. Lucian had a mother listed on his birth certificate and a line where his father’s name should have been. Less than 1% of “Ceaușescu’s children” were in fact actual orphans.

The communist legacy started with a decree passed in 1966, which banned abortions and severely restricted birth control. One year later, the annual birthrate in Romania doubled and experts estimate the annual number of abandoned children doubled with it. The children were housed in institutions scattered all over the country. In 1989, this residential infrastructure consisted of 65 infant centers (for children aged 0-3), 224 orphanages for preschool and school age children, 113 “special education” kindergartens and schools, plus other institutions for children with “recoverable deficiencies” and 33 hospital-homes for children deemed irrecoverable.

Overcrowded and lacking properly trained staff, these institutions were ripe for abuse, accidents and even death. At the fall of the communist regime, when poverty engulfed the entire country, the nutrition of children in institutions suffered dramatically. To treat anemia caused by malnutrition, doctors resorted to blood transfusions at a time when Romania didn’t test blood for HIV because Ceaușescu considered it a disease of the decadent West. Children in infant centers becoming infected with HIV in hospitals in the late ’80s were not officially diagnosed and died hidden away, with no treatment. It was only after the Revolution, when foreign journalists photographed sick children, that the country admitted it was an epidemic. In the ’90, half the cases of HIV/AIDS in Europe came from Romania.

Constanța, the city where Lucian was born, was one of the biggest HIV hot-spots in Romania. His papers say he was abandoned at birth in the County Hospital and in 1988 was placed within the state infant center in Cernavoda. Testimonies of foreigners who volunteered there speak about a center with hundreds of children left to wallow in their own feces, fed a think milk porridge, severely underdeveloped and almost never lifted from their cribs with metal bars.

If this is what the first years of his life were like, for Lucian has no memory of Cernavodă, the effect of this lack of affection and care can be permanent and prohibits the development of secure attachment to a parent, as shown by numerous neurological studies on institutionalized children. However hard some adoptive families tried to heal the traumas of Romanian children, those first years of severe neglect left some of them unable to ever trust or love their new family.

Lucian doesn’t think he was ever in Cernavodă because he has visited the town now, at 36, and didn’t feel anything. In his earliest memories he sees himself wandering through a Bucharest where the House of the People (today’s Palace of Parliament) is still under construction. “It’s like I’m in the middle of the Revolution and I can’t find my family, then everything goes dark,” is how he tried to describe it. It’s a mishmash of images he saw online that his mind used to fill in the gaps. He has replayed them so many times in his head that they now feel like his own memories.

When he was little, Lucian knew nothing of the HIV epidemic in the city. He saw a negative HIV test in his adoption record and for many years had wondered why he was tested before being taken to Belgium. He found out later on, as an adult, that back then an unsterilized hypodermic needle or a blood transfusion could have changed the course of his life.

When he lived in the Cernavodă Center he didn’t know how lucky he was to pass the brief medical examination he undertook around the age of 3, which led to his transfer to an orphanage for preschool children in Constanța. He learned from reports that if he hadn’t been able to speak, to walk, to use the potty or had been physically underdeveloped, he could have easily been deemed “irrecoverable” and could have ended up in a hospital-home.

The Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of the Romanian Exile (IICCMER) and the testimonies of survivors and employees of the system have shown that some children came to bear that permanent label even though they had no disability at the time of admission, or had vision or hearing impairments. Hospital-homes were the worst places children could end up after that scant medical assessment. In these institutions they were no longer taught how to eat or dress themselves, they had no education and they would degrade, with no chance of ever leading an independent adult life.

Names like Cighid, Sighet, Siret, Tătărăi, Plătărești are still horrifying to hear today, 20 years after they were closed. These are places where hundreds of children died of neglect and cemeteries located nearby stand as evidence.

To Lucian, communism is a mixed concept. He knows that some of the major landmarks in Romania were built then. He likes the House of the People and the Transfăgărășan mountain road. He was too young to understand what life was like outside orphanages. He’s even imagined that maybe he is the son of some bigwig in the Communist Party and that’s why he can’t recover his identity. For him, the ’90s are the “Wild West” where atrocities were committed and no one was held accountable.

This summer I volunteered at the Museum of Abandonment, a digital museum that recovers and digitizes the archive and memory of institutionalization. It is a private project of an NGO which, unlike the state, is trying to unearth this past and become a virtual space for dialog between the “invisible community of abandoned children” and the general public. Dozens of student volunteers plus historians, anthropologists and communication experts are working on a digital map of all the orphanages, with information and pictures for each one.

As a volunteer, I viewed hundreds of photographs and hours of video footage from hospital-homes that aired internationally after the death of Ceaușescu; Romania was one giant orphanage. I saw preschoolers that looked like infants, children who were sitting up for the first time ever, foreign volunteers teaching Romanian staff to touch the children, to speak to them, to lift them up from their beds for at least 10 minutes each day. There were employees who found the requirements ridiculous, but there were also people who were happy to finally learn methods that could actually work. As the child protection system was a massive employer and factories were shutting down during those years, the last thing people wanted was to be left without a job, so staff tried to take part in the reform.

Children in hospital-homes were kept tied to their beds, dressed in mere rags, hungry and cold. If they couldn’t walk by themselves, they never saw the sun. Those who went out in the yard are seen rolling around in the mud or eating grass, supervised only so they wouldn’t run away. On winter, in Plătărești, volunteers found dozens of restrained children whom nobody had visited as it had snowed hard and no employee had been at work in days. In these institutions, children died of pneumonia, self-inflicted wounds, malnutrition and countless accidents – a girl at Sighet slipped into a hot tea bucket and died of her severe burns. At the hospital-home in Cighid, in the period 1987-1990, 138 children died out of the total of 183 children housed there. Most were between 3 and 5 years old.

The buildings for children without disabilities sometimes hid a type of savagery that occurs when hundreds of children are forced to live together with not enough responsible adults around: obsessive body rocking from lack of affection, older kinds making younger ones fight among themselves for fun, sexual abuse, employees wearing white coats to keep their street clothes from getting dirty, thus amplifying the sickly environment feeling.

This degree of neglect is a reference point in many of the studies on attachment and children’s need for attention and affection. Studies such as the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), which analyzed the neurological development of children in six infant centers in Bucharest compared to that of children placed in foster care or growing up in regular families, concluded that institutionalization in the first years of life has severe effects on intellectual capacity and social and emotional behavior and increases the risk for psychiatric imbalances.

Studies like these convinced us to ban the institutionalization of children under 2 years of age to prevent such tragedies. From an ethical standpoint, BEIP was criticized because the experts were aware of the toxic environment in which the researched children were kept at a time when other orphanages were being shut down.

Lucian spent his first three years in such an iron crib, first in the hospital and then in the infant center. He thinks he was quite sheltered from abuse at the orphanage for preschoolers in Constanța, where he lived until the age of 7. He remembers he had friends, that he didn’t like to take his afternoon nap and the caretakers would yell at him to make him close his eyes and go to sleep. He thinks he remembers they had a TV that they all watched and perhaps that’s where he got the idea he wanted to be adopted in America. He knows he wanted to be adopted there because he thought it was “the country of all riches”.

The story of the “orphans” was so heavily featured in the media and so indelibly tied to foreigners’ desire to save them that it was well known even to children in institutions, at a time with no internet. As early as the first months of 1990, Romanian airports were filled with families that wanted to take the children out of orphanages and give them a different life.

After less than two years of democracy, Romania had become the source of at least one third of children adopted annually worldwide. Over 10,000 children had already left the country. Other former communist countries allowed international adoptions as well but, in the media, the urgency to save the children in Romania seemed greater.

Faced with thousands of requests from foreigners, Romania attempted to set up its international adoption legislation. It set up the Romanian Committee for Adoptions and decided that only children in institutions could be adopted internationally and only after a six-month period of trying to place the child with an adoptive family in Romania. The legal definition and justification for foreign adoption was that the measure was “a means to ensure harmonious development for the child deprived of the protection of his natural parents, if the child cannot be adopted in the country.”

In the statements in Lucian’s file, the Schepers say they want to give him a chance to a better life than the one in Romania and that they grew fond of him when he was 6 and came to Belgium on vacation, with 24 other colleagues from the orphanage.

Vacations abroad in those years were opportunities for institutionalized children to see what family relations look like and to see what life looked like beyond their mammoth buildings. The trips were sponsored by foreign parents’ communities or religious organizations who wanted to bring joy to the children for whom they sent humanitarian aid. But there were also vacations paid for by foreign adoption agencies – a means of presenting their “offers” without the need for interested families to come to Romania. A former caretaker told me, “They wouldn’t send just anyone on these vacations. Only the whitest and cutest children were chosen. If their skin darkened in the meantime, they wouldn’t be chosen again the next year.” Not all vacations ended with adoption, sometimes they were a chance to become friends with borrowed families willing to support a child long-term with gifts, help with studies, career guidance: a chance to not be completely alone in the world.

Lucian doesn’t remember much from that two-month vacation and doesn’t think he spent much time with the Schepers. He knows they were friends with another family that brought humanitarian aid to Romania and that hosted children on vacations. He remembers it was this family that brought him to Belgium after he was adopted and turned him over to the Schepers at the airport. “But they were good people,” he told me. “They adopted a colleague of mine. He had a very good life with them. This was not my case.”

It is from that vacation that he has a list from the orphanage with names and dates of birth. He found it one night during his teenage years when he secretly peeked at his adoption file and took it out of there, without understanding why the Schepers had it or what it meant.

Lucian left Romania right before he should have been transferred to a home for school-age children. Instead, he started school in a new country, with a new language and an unknown family. He says it was a failure because he couldn’t understand anything that was said to him and the other children mocked him. The parents took him out, enrolled him in language classes and then sent him to a different school, where the majority of children were immigrants. He thinks he stopped speaking Romanian because he was too ashamed.

The years when Lucian was forgetting his native language were the years when Romanians translated, drove people around, exchanged dollars and pushed open the doors of institutions in exchange for a fee from families seeking to adopt. There were contact sheets and informal guidelines on what to do when seeking to adopt a child, such as the door-opening power of cartons of Kent cigarettes, coffee, jeans or diaper rash creams.

In July 1990, George Harrison, former member of The Beatles, launched the charity album Nobody’s Child with contributions from artists like Elton John, Billy Idol or Eric Clapton. The lyrics „No mama’s arms to hold me/ No daddy’s smile” went together with footage of Romanian children crying in their tiny cribs, with bottled tied to the bars so they would feed themselves. The proceeds from album sales went to the renovation of orphanages and the training of staff in Romania.

One day while I was volunteering at the Museum of Abandonment, while going through a bunch of reports from a green folder from 1992, I came across a pink note titled “To all Band, Crew & MJJ STAFF”. It was dated 1 October and was an artifact of Michael Jackson’s concert in Bucharest, a show attended by over 70,000 people. The artist’s team chipped in and donated all the Romanian lei that had left in their pockets to the orphans.

The mirage of international adoptions as a means to protect the children also led to situations that are hard to watch even 30 years later. In a scene from 1991, documentary filmmaker John Upton gathers up the children at the Sighet hospital-home and tells them only the one who hear their names will be able to go to families in the United States. Some of the viewers decided on the spot they had to do something. There were women who sent their husbands to Romania on a clear mission: “Take as many as you can! 2-3, boys, girls, it doesn’t matter! We have to save them.”

Romanian newspapers published the top of adoptive countries – USA and Italy – in their “Did you know” columns, next to horoscopes and epigrams. Femeia magazine wrote in 1996: “Faced with this mind-boggling commerce of human beings we cannot help but wonder where the sudden ‘passion’ of foreigners for Romanian children, especially since in some cases the adopted little ones are handicapped”. The article details a trafficking network, which included Rodica Samoilă, manager of the Giurgiu hospital. Samoilă had facilitated the foreign adoption of 12 newborns by convincing their poor or underage mothers to give them up. In exchange for this service, she received an average commission of $2,000 per child. In the interview she gave the magazine, the doctor investigated at large said nonchalantly: “It seems to me a humanitarian act for a child to be sent to a real family rather than be left to wander the streets or end up in an orphanage.”

Because more and more people wanted to adopt Romanian children, a black market flourished around convincing vulnerable families to give up their babies or even to have babies for export. Experts estimate that a quarter of the total of international adoptions were of children who didn’t live in orphanages but came from vulnerable families that gave them up.

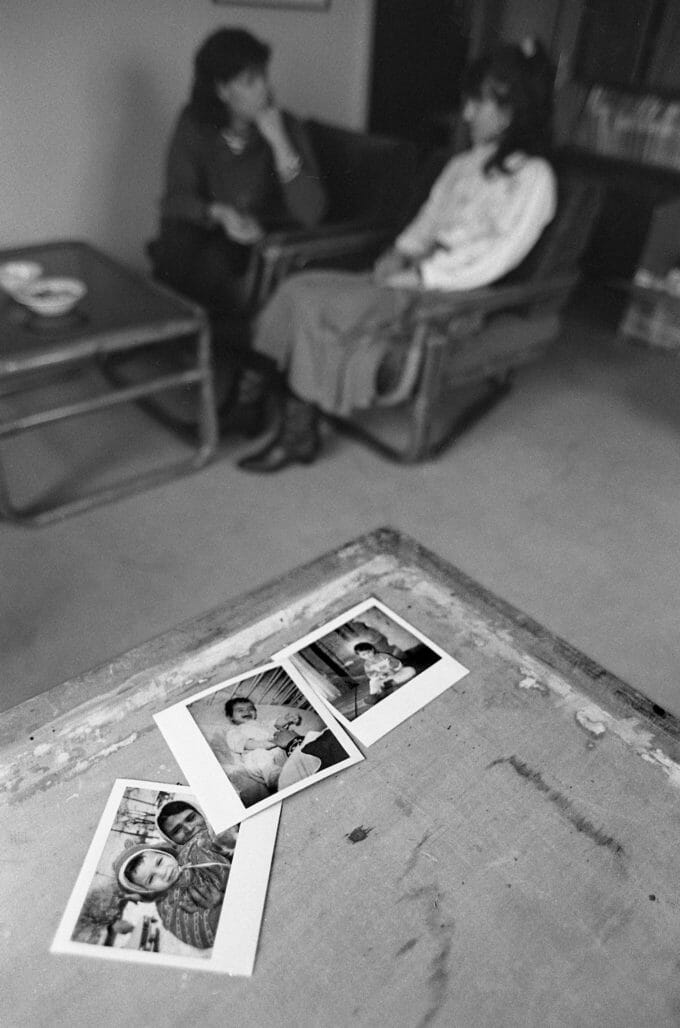

The middlemen approached foreigners in hotels, on the street or at the airport and showed them photos of babies. American journalist Michael Carroll photographed deals made for thousands of dollars in huts, basements and hotel rooms. Outside the Telephone Palace in Bucharest he saw how a little girl was sold for a car, a VCR and $1,200. In another shot, a man brought a chicken to get the adopters to end the negotiation.

It wasn’t just Romanians who profited from this black market. In his book,Picturing the Possible, Carroll writes that he saw an American woman in a Bucharest hotel selling babies for $6,000 a pop. She had three bundled up in cardboard boxes and one in a basket. When she noticed him take out his camera, she kicked him out of the room. The future parents, Carroll writes, were lined up in the hallway and were also hostile. “They had decided to ask no questions about where their children came from.”

In the spring of 2000, BBC reporter Sue Lloyd Roberts went undercover to visit an infant center in northern Romania, claiming she wanted to adopt. The manager told her a child could be sent to the UK with no problems, that documents would be falsified and the biological parents tricked into consenting.

Numerous voices said Romanians were selling their children during those years, not just through these unofficial transactions, but through the legalized system as well. Roelie Post, assigned by the European Commission to oversee the reformation of the child protection system in Romania between 1999 and 2005, was shocked to find, nine years after the Revolution, that the European Union had invested over 100 million euros in the child protection system reform but orphanages still complained they lacked enough food, furniture and trained staff.

“Where did all that money go?!” Post asked when she saw that relief kept coming from around the world. The EU, World Bank, NGOs, numerous embassies and private companies were donating for clothes, toys, furniture, the renovation and reconfiguration of those massive buildings. And yet Romania continued to abandon and export children, claiming this was the best protection available.

Post kept a journal from the very first day she arrived in Romania; she published it in 2007 as Romania for Export Only. “Children were being offered on a silver platter,” she wrote. “Catalogs with photographs, date of birth and short descriptions such as: healthy, cute, intelligent, minor disability, ready to help out in the household. The American agency United Families offered the most detailed indication of the costs involved: between $20,000 and $40,000.”

When Post started following the money the European Commission was giving Romania for reform, she found a point system through which NGOs that received EU money for humanitarian work were at the same time involved in the adoption industry. A family seeking to adopt a Romanian child would pay tens of thousands of dollars to a foreign agency, which in turn paid a Romanian NGO, which then paid a share of that money to child protection departments. Depending on how much they invested in the state care system, agencies would receive a certain number of adoptable children.

The Romanian state, which was supposedly protecting these children, received money to declare them fit for adoption and it was all legal. The state used that money to organize projects for children in institutions, renovated and outfitted buildings, trained staff and ran programs to prevent child abandonment.

“Adoptions answered foreigners’ needs to receive European children, as white as possible,” she explained. This was primarily done for profit, not in the interest of the children.

Find out more: the organizations involved

In an online interview at the end of this summer, Roelie Post told me Romania’s image was just as disastrous 10 years after the Revolution. “The disaster was due to NGOs which practically drove the bus of the system and foreign adoption agencies and had every interest to maintain the chaos.”

Over 200 foreign adoption agencies, many of which were Christian organizations, had protocols with NGOs and adoption agencies in Romania. The most vocal in their stated mission to provide families for all the Romanian “orphans” were, according to Post: Amici dei Bambini, SERA France, Holt (an American agency that had “counseling” offices in Romanian maternity hospitals and convinced mothers to give up their babies right after birth). Many of these agencies are still in the adoption business today in other countries facing humanitarian crises. The Romanian NGOs Post says were actively involved in international adoptions were: Copiii fericiți, NOROC, Copiii Lumii, Fundația Irene, Speranțe, Ocrotiți Copiii, Stuart – names that don’t ring much of a bell today but in the early 2000s were part of a list of over 100 Romanian agencies, many of which were founded by the very lawyers handling the adoption process.

But pro-adoption lobbyists continued to talk about „Ceaușescu’s children”. In a discussion with a representative of the US State Department who used the same old tired phrase, Post burst out laughing: „Ceaușescu is long dead and buried. These are Băsescu’s children!”

To gather evidence on the absurdity of exporting children, Post traveled throughout rural Romania and talked to vulnerable women who had lost their parental rights. She listened to mothers who had put their children into state care to make it through the winter. Post also told me that in the talks she had with teenage girls in orphanages, some of them told her they were terrified by all the foreigners visiting the institution. “They had to line up, dressed only in tights and tank tops, for foreigners to inspect them.” Adoption was at the same time the promise of a loving family in a rich country and the nightmare of being exploited.

“International adoption was a sort of Russian roulette,” said Mariela Neagu, who this year published Voices from the Silent Cradles, an Oxford University research project, a comparative analysis of the quality of life of 40 young people aged approximately 25 who stayed in institutions, grew up in foster care or were adopted, both in Romania and internationally. The purpose of this research was to understand, from the children’s point of view, how they lived through the reform of the system and how that influenced their personality and identity.

Neagu worked as an expert in the reform of the child protection system for the European Commission in the early 2000s and was at the center of the awareness raising campaign “Casa de copii nu e acasă” (A children’s home is not home), which aimed to change Romanians’ collective mentality, strongly influenced by the communist propaganda that had claimed state institutions were a healthy environment and even preferable to disorganized families.

“The system was incredibly unhealthy and allowed numerous irregularities of all kinds, such as the adoption of teenagers – as in the case of a girl I interviewed for my research who was 17 when she was adopted in Italy and lived in a barrack, forced to clean and be a kind of Cinderella for that family,” Neagu said.

Of course, the children could be lucky enough to have the family that had paid thousands of dollars for them to be a balanced and loving one. But leaving child protection to chance was deeply immoral, the researcher said.

While thousands of small children continued to leave the country in the early 2000s, Lucian was entering his teenage years in Belgium. He had received a B.U.G. Mafia music tape from a friend and he liked the beat but didn’t understand a word of the lyrics. He was curious to know more about Romania, but he was utterly consumed by the exhausting fights at home.

He doesn’t think his adoptive parents ever loved him. They only liked him when he was little and did everything he was told. He didn’t feel he was treated the same as the family’s five other children. He told me he was not allowed to touch his father’s laptop unless another sibling was present and he would be yelled at if he disobeyed the rule. He was the only one sent to the shops or made to help with renovation projects and housekeeping. He said he was sexually molested at the age of 12 by a sister and one of his brothers and that his adoptive father forced him to keep his mouth shut when he tried explaining to him what was going on. (In 2021, he described those episodes in ample details in a police complaint in Belgium, but the case was closed on lack of evidence.) He tried to kill himself more than once. He got into monstrous fights and tried to grab his adoption papers from his father’s hands.

In an attempt to appease him, his parents promised to take him to Romania to meet his birth mother. In 2004 – Lucian still doesn’t understand who helped them contact her or how they found her – his parents started emailing with the woman listed on his birth certificate. They said he could talk to her on the phone one weekend, but he didn’t trust her when he heard her voice and he didn’t understand Romanian anyway, so he didn’t know what to say. He was convinced they had someone pretend just to shut him up. And yet, a few months later, his parents accompanied Lucian to meet his biological mother in the lobby of a hotel in Constanța.

“She had a flower in her hand, as if we were at a funeral,” Lucian described the meeting. “I felt no connection whatsoever. I told them right then and there: Are you kidding me? This can’t be my mother. We look nothing alike, she’s blonde and white. I’m much darker skinned. She’s not showing any emotion upon seeing me again. What kind of spectacle is this?”

He is convinced you can feel if someone is your kin and that a real mother will never be cold and indifferent. He told me he felt nauseous when this “so-called mother” gifted him a framed photograph of his adoptive family. “Who does that?! It’s sick and stupid!”

As the first adopted children were nearing adulthood, the European Commission warned Romania it would no longer tolerate the wasting of renovation money for institutions while the country continues to export its abandoned children. Under pressure, Romania introduced a moratorium on international adoptions in 2001, then officially banned them altogether in 2004.

The closure of the Romanian market also meant disappointment in particular cases: children who knew they had been chosen but were now unable to go because the legislation changed, siblings who could not be reunited, couples that had grown fond of a certain child and were barred from adopting after months of visits and hope.

The system in 2004 was far from a rosy picture. We still had institutions with hundreds of beds, abuse was still rampant and children were still being abandoned by the thousands each year. But reports by the European Union had shown that international adoptions created a vicious circle: as long as it was so easy and profitable to send our children abroad, Romania had no real interest to undertake a solid reformation of the system. It was time to stop.

Beyond the corruption around the phenomenon, adoption was for many children a chance to have a loving family with whom they tried and sometimes succeeded in healing the traumas of their first years of life.

One mother in the US wrote on the forum of Pound Pup Legacy, a global platform committed to exposing “the dark side of adoption”, that she volunteered at an orphanage in Romania and adopted two girls from there, convinced that leaving them there would have meant certain death. “My daughter was 11 and had never got up from her bed. My youngest daughter is in special education due to neglect. She doesn’t speak and will never be able to read. If I could sue Romania for what it did to them, I would in a heartbeat.”

Many youngsters in online groups write about the “perfect family” they had and how adoption healed them from the terrors they lived with in orphanages – fear of the dark, compulsive eating and hiding away food, nightmares, inability to trust others.

Izidor Ruckel is one of the most visible figures of the adoption phenomenon in Romania. Adopted in America from the hospital-home for irrecoverable children in Sighet, he speaks three languages, is the manager of a fast-food restaurant and an activist for the rights of the formerly institutionalized. He published a book, Abandonat pe viață (Abandoned for Life), in which he writes he was extremely happy that he was chosen to be adopted. The first moment when his family understood it would be difficult for him to adapt to his new environment was when they tried to click a seat belt on him in the car. Izidor bucked until he tired himself out because being restrained reminded him of being tied-up in the hospital-home and he didn’t understand what they were explaining in English. However loving and understanding his adoptive parents were, Izidor says living in a family environment made him feel angry after 11 years of knowing only violence. He didn’t laugh, didn’t like to be touched, he tore the photographs in the house. Izidor’s advice to people like him is to accept who they are and that they won’t be able to let go. “You will never be able to let go. I’m drawn back to it for the rest of my life,” he said in an interview.

These are the pros and cons of international adoptions. Some families weathered the rejection storm from their adopted children, others reproached them for being ungrateful, withheld their affection and some even gave up and sent them back to Romania when they felt they couldn’t take any more. It’s hard to generalize and I haven’t yet spent enough time listening to those who were at the center of this story.

For some of the adoptees, the healing of traumas came with a need to understand where they came from. In the past 10-15 years, like Izidor, they started asking questions, visiting the country, seeking their families, colleagues and former caretakers, writing books and shooting documentaries. The lucky ones who had families that supported their search and that adopted them at very young ages came back more out of curiosity and to fill an identity gap, without being destabilized by this reunion. They had a family and a life to go back to. Their identity did not depend, as in Lucian’s case, on finding their roots.

“Identity is very important,” says Mariela Neagu. “But because many people have it, they don’t necessarily bother to understand the implications of what it means to not have it.”

Not having an identity means Lucian is not certain of anything: Where did I live in the first months of my life? What was it like there? Did anyone hold me? Did anyone harm me? Why was I adopted into this family that doesn’t love me?

Lucian’s refusal to accept his adoptive parents is common, even if there hadn’t been any kind of abuse, Neagu explained. The urge to know their biological family starts manifesting itself in adolescence for many youngsters and is even stronger the more their adoptive family refuses to support it. Relationships endure where the adoptive parents don’t pull back, don’t blame their children for being ungrateful and stand beside them though the pain of the unknown.

Lucian’s anger is most apparent when you look at his adoption file, consisting of around 40 pages of photocopies of typewritten documents that have yellowed with age. He gathered them all up in a red plastic folder and has scrawled on nearly every page, in capital letters: “BULLSHIT” and the Romanian “RAHAT”.

“Those children in my research who were adopted internationally had very strong identity issues, which impacted their day to day lives both professionally and personally,” Neagu told me. “They entered toxic relationships, had trouble holding down a job. Identity was an obstacle in their lives and they all wanted to know more about Romania. Many were no longer in contact with their adoptive families at the time of our interview, while those who stayed in the country had relationships with their adoptive parents.”

As deprived of opportunities or resources as the life of those who stayed in Romanian institutions was, if they had at least one adult to attach themselves to and who would guide them, the youngsters found the strength to understand their wider context. Their life story was hard, but they had a story.

The cultural identity of a young person adopted in a different country doesn’t develop gradually, but based on stereotypes. They were often told or saw in the media that they were born in a hopeless place where children were tortured and their mothers were so poor that they were willing to sell them. This is what Lucian says has felt strongly his entire life: a reproach that he was not grateful for being saved. “Son of a whore”, “You would’ve ended up in the sewers if it weren’t for us”, “I wish we’d never taken you in” are some of the insults he says his family hurled at him.

International adoption brings with it, besides the potential chance to a better life, a string of certain losses: your name, language, extended family, citizenship. The older the child is at the time of leaving, the list of losses is longer – a favorite educator, the friends you played with, a second helping from a favorite dish the mane of which you forget. Identity becomes an accumulation of struggles to belong. “I belong to the universe,” a young woman told Neagu. Another youngster said: “I don’t feel American at all, I don’t identify myself with this country at all. I just exist…”

Lucian couldn’t say where he feels more at home. He has always felt more at ease among immigrants, where people are less likely to ask intrusive questions about his name or where he comes from. He started his search in adolescence hoping to find his real mother and his real identity. He imagined this wonderful family that was also looking for him and hoped in the happy ending that would bring him peace, self-acceptance and the love of family members.

After he met his birth mother and was so disappointed that he hadn’t felt anything, he was convinced that his entire existence has been a lie. “My case is not like all the others,” he told me in our first interview. “It’s very complicated and mysterious. I was kidnapped from the hospital or from my real family and they gave me this identity just to cover it all up.”

Not all identity searches lead to deliverance. Sometimes they keep you imprisoned, especially when you don’t like what you find. As long as you keep searching, you can still hope you may one day find a more satisfying narrative.

When I asked Lucian if he still had a contact for the woman who was presented to him as his biological mother, he said he didn’t. But he did show me the answer he received from the National Authority for the Protection of Child Rights and Adoptions (ANPDCA), where he requested information regarding his record. ANPDCA has inherited the archives of international adoption records and also helps adoptees reconnect with their biological families if the families consent. The authority’s website recommends that all adoptees seeking information about their personal history should “seek prior counseling, given the emotional implications” of the process.

A team from ANPDCA contacted his biological mother and summarized their exchange in an email:

“Mrs. Voinea made a series of affirmations that are not supported by documents or other evidence. (…) She said that you are not her son, that her biological son was ‘stolen’ by his biological father, a person of ‘high standing, with an important position’ about whom she provided no information. (…) Mrs. Voinea said your biological mother died giving birth to you. In this context, she decided to give you up for adoption.

Your biological mother refused to sign a written statement containing these affirmations, did not wish to provide her telephone number and refused to sign a consent form allowing us to reveal her personal information.”

Lucian did not seek counseling prior to receiving this answer and immediately clung to the incoherent narrative. He read the email to me several times, curious to see if I understood it as he did. “So she admits she is not my mother and that she stole me from the hospital! My mother died at birth!” he told me. He was trying to process the news that he would never meet his real mother, even though the counselor at ANPDCA explained to him repeatedly, via email and on the phone, that this woman is his biological mother and that she could be denying it for a number of personal reasons.

Lucian preferred to believe that his mother was dead. But even so, he still wanted to know who she was, if he had any other living relatives and, most of all, he wanted those who gave him a false identity to be punished.

He filed a police complaint accusing Elena Voinea of human trafficking and attached the answer from ANPDCA. Shortly after that, he was informed that his complaint had been forwarded to the Medgidia Police, as that is where his mother now lived.

Meanwhile, I scoured the internet until I found dozens of Facebook and Twitter accounts, all belonging to Elena Voinea, with the photo of a man for a profile picture, as well as a few blurry pictures of her. I asked Lucian if he recognized her and he confirmed with astonishment that it was the woman he had met as a teenager. Because on one of the accounts Elena had posted the picture of an envelope with a visible address, a few days later we both got on a train to Medgidia.

I will describe a few moments that only added to the confusion, but which are relevant precisely because they show how bizarre such a search can be.

We stopped first at the police station because Lucian was hoping they would summon Elena to the precinct or at least would go with him at that address, since he had filed a complaint against her. It was two wasted hours that made him even angrier because of the well-known answers: “That’s how it was back then”, “It’s not something we can help you with.”

We went alone towards Elena’s block, passing by a park and a mosque that made Lucian smile. “Medgidia looks like a nice and quiet place. Multicultural?!” he told me. Outside the ground floor apartment we both took a few steps back and photographed the tag on the door, which had another name added in blue ballpoint pen: Schepers.

Lucian knocked. Elena opened the door, intrigued.

“I didn’t know who you were looking for. I saw you out the window,” she said. Because she didn’t seem to recognize him, I explained to her that Lucian had come from Belgium and would like to ask her a few questions if she didn’t mind.

She started laughing and asked him: “You still haven’t learned Romanian?”

Then she invited us in and rushed out the door to take out the trash. From a distance, she shouted that she was taking advantage of the fact that we were there because otherwise the neighbors would come in and steal her things. “They even replaced my door when I was away! And they replaced my chairs with older ones! They will steal anything!” we heard her say while we were both staring at the couch where she had told us to sit. On the red cover of the couch were three big rocks.

We were scanning the room trying to make sense of things, but we couldn’t focus as her phone left on the table played a religious service babbling something about demons. When she came back, she whispered to me that she was listening to the service because there were all sorts of devils making noise at night. I translated into English for Lucian hoping he wouldn’t think I was making it up. He laughed and said it was obvious this couldn’t be his mother.

“He says you’re not his mother,” I translated for Elena.

“Well, I’m not!” she laughed too. “You and I are two parallel lines that never meet.” She then explained that she felt no connection to him when they first saw each other. “I was trying to touch him but he kept pulling away.”

It was the same now. Lucian pulled back every time Elena tried to touch his leg, take him by the hand or tried to sit next to him. From a distance, he asked her questions and she answered them, whispering and going off on tangents, telling the same story she had told the people at ANPDCA.

In short, her story was this: she was being courted by several men. One was named Lucian and another Ion and that explained his name. Ion supposedly came to her door one night, drunk, and pressed her to have a child with him, even though she didn’t like him. Nine months later, she gave birth to a boy at the Constanța County Hospital. After giving birth, everything turned black and she fell asleep. When she woke up, she was alone in the hospital room. That’s how she found out that Ion, a very influential man, had come and taken her baby boy. To keep her quiet, a nurse took her to a room where they had ten abandoned children and told her she could pick one.

“So you stole me!” Lucian interrupted her, shouting.

“No, wait, I didn’t steal you! I left empty-handed. I didn’t take any child!” Elena defended herself laughing.

“Yes, you did! You think it’s funny that you stole a child and ruined my life?”

Their discussion went on confusingly for over two hours.

For Lucian, however, things seemed crystal clear: his mother had died at birth, his father was, according to Elena, “a sailor, dead at sea”, and he had been mixed up in this story to cover up a scandal that had nothing to do with his real family.

I asked her whether she was willing to go to a DNA testing clinic to put Lucian’s suspicions at ease. Elena got up from the couch and asked serenely: “What do you want? Hair? I’ll give you hair.” Then she took a pair of scissors and snipped a blonde lock and handed it to Lucian. He took the clear plastic wrap off his cigarette pack and motioned to her to put it in there. He didn’t want to risk contaminating the DNA sample. He wanted definite proof that his woman, who was laughing while talking about the painful story of his life, was not his mother.

We congratulated ourselves that day that we found her, that she opened the door and that all we had to do now was wait for the test result.

But aside from the whole bizarre circumstances, something was amiss in the story Lucian had been telling me. Elena said they had been in touch years ago. She showed me payment orders from the few times she had wired money to him in an account in Belgium. He denied ever getting it and said his adoptive family had surely taken it. What’s more, they had seen other again ten years ago, helped by a nephew of hers who had brought him to Medgidia. I asked why he hadn’t mentioned that he knew, in fact, where to find her. He apologized saying it was many years ago and he wouldn’t have found his way to her building and Elena’s nephew isn’t speaking to him anymore and wouldn’t have helped us.

After we got hold of the lock of hair (“the demon hair”, he called it), Lucian thought it would now be just a matter of days until he had the proof he had wanted ever since he’d first met Elena. He notified the owner of his rental apartment in Bucharest that he would be moving out. He notified his employer he wouldn’t be coming back to work. He wanted to go back to Belgium and sue everybody.

His euphoria paled a few days later, when he got a phone call from the lab and was told the hair should have been cut from the root, but the safest bet would be a saliva test. He had to hang in there until he had proof so he canceled his plans to leave and started looking for a new job. A few days later he asked me to help him try to get another DNA sample.

I too was itching to know the truth. When you hear stories about the corruption surrounding adoptions, it’s only natural to start seeing conspiracies. And when you get blunt answers from authorities, you begin to wonder if they might be hiding anything – the Constanța County Hospital which took two months to tell Lucian his name was not in the hospital’s archives, even though his papers attest he was born there; the social inspection agency that told him it had no information on his biological parents, although Lucian had inquired abut his record at the Cernavodă infant center; the confusion of police workers in Medgidia when we asked why Elena Voinea was listed as childless in their database.

During the same period, I talked to Laurențiu Garofeanu, the director of a documentary still in the making – Lost and Found – which tells the story of a young woman adopted in the USA, who learns that her mother and grandmother had sold her to a middleman when she was a baby. Everything was coming together in an absurd story that leaves room for the suspicion that the mother listed on your birth certificate may not be your mother at all.

So we returned to Medgidia looking for certainty. There is no point in recounting this second visit, but two details have stayed with me. The first is that the door tag with the added Belgian name had been taken down. Elena didn’t answer the door for more than one hour even though we knocked, called out her name and slipped her a note under the door. Lucian was afraid something might have happened to her. I felt concern in his voice when he called out to her repeatedly: “Elena, are you OK?”

When the woman finally opened the door, everything was even weirder than the first time.

She grabbed me tightly by the hand and took me to her bedroom to show me that her upstairs neighbor was washing her balcony and had soiled her windows. On the nightstand beside her bed I saw the second unforgettable detail: a plastic baby. Elena told me a priest had given her the doll after she had been to confession, to help her make her peace with the fact that she would never have a child.

Lucian interrupted our bizarre home tour to get the saliva sample and get it to the lab in Bucharest as soon as possible. He had no patience to listen to her stories, he didn’t want to be around her and was confident that this was the day when everything would be cleared. We promised each other we’d go out to celebrate if the test came out negative.

One evening in October, when we were both on the edge of our seats awaiting the DNA test result which was due the next day, he sent me a joke about how his adoptive father would make an ideal partner for Elena and that they should get married at the Cernavodă infant center. “I will officiate the ceremony and you can be a witness,” he recorded himself in a fit of laughter. I didn’t understand how he could be making jokes when the situation was so tense.” We have to laugh, Ana. Otherwise we lose our minds. I’m a positive guy generally but I admit I’m so very tired. I want this to be over.”

Then he thanked me for listening to him during this time. “It’s nice when someone hears you out and stays with you,” he told me. Alone, in a foreign country, he keeps his few friends posted with video calls. Many have told him he would never find out the truth and it would be best to give up. One by one, people grew tired of watching him struggle. “But I won’t give up, Ana. I’m a beast and I will fight for the truth until my last breath.”

The next day, he sent me a screenshot of the result interpretation. I had to read it three times because I couldn’t understand a thing from all the excitement: “Based on the genetic analysis of the 15 loci indicated, the alleged mother cannot be ruled out as the biological mother of Schepers Lucian Ionuț as the samples present similar genetic markers.”

Lucian was rattled and confused. “Cannot be ruled out doesn’t mean it’s certain, right?” he asked me. “What kind of wording is this? Why doesn’t it say clearly positive or negative? Fuck this lab!”

If you’ve never seen a DNA test before, the wording can leave room for hope. A few minutes later, he received an email with the result interpretation in English, which also stated the compatibility rate between the two samples: 99.9%.

During these months, I have also tried to talk to other members of Elena’s family and I have witnessed Lucian’s phone conversations with members of the family whom he was quite aggressively pressing for answers. The nephew who took him to Medgidia 10 years ago wrote to me saying he thinks Lucian has inherited his mother’s mental issues and he is not interested in talking to him. Another nephew of hers calmly explained to Lucian that Elena had always been a very private person, she hadn’t attended anniversaries and major family events and that no one had known she had had a child until he showed up in Romania.

The sad truth, foreshadowed by the DNA test, is that Elena gave birth to Lucian and abandoned him for reasons that seem impossible to reconstruct today. She has spent her entire life alone, trapped in her theories about devils and people that want to do her harm and took refuge on Facebook, where she writes about an imaginary boyfriend she is always expecting for dinner.

I have tried to understand whether Lucian can accept this scenario but he said he doesn’t trust the lab, that it must be a mistake and he will take the test again elsewhere.

He spent his first night with the truth pursuing other scenarios, hoping to find some sense: “Maybe I am related to her but that doesn’t necessarily mean she is my mother, right? Maybe she’s my aunt?”; “Maybe she was raped and she lost her mind and so never accepted that he had a child?”; “Maybe somebody faked the test. These things happen.”

So far, Lucian’s entire goal was to prove Elena was not his mother, because it’s painful to accept that you have been abandoned willfully or that the roots you idealized are in fact anchored in a person that seems lost.

Still, the day he got the result he decided to send her a text and for one moment give a chance to the idea that some terrible trauma made her lose her mind. He wrote that the test showed she is his mother and asked: “Why can’t you accept that I’m your son? What happened to you, Elena?”

She didn’t reply.

I asked him if this message was his way of asking for a little acceptance, but he refuted the idea. “I wrote that just to try and find out more. I refuse to believe I am in any way related to this Voinea family.”

The phenomenon of international adoptions may seem like a distant past when we look back from a present in which we have shut down the majority of old-style institutions and we have become a deinstitutionalizing model for other countries in the Black Sea region.

Today Romania houses just 10,000 children in residential centers. More than half of them are teenagers who will need social services to support them in their transition towards independent living and to protect them from human trafficking and exploitation. The number of children abandoned in maternity hospitals amounts to 400 a year. Ten years ago, that number was triple. Each year, 1,600 Romanians adopt children and over 11,000 are foster parents paid to ensure a family setting for vulnerable children.

But this is also a present in which Lucian and other hundreds like him are knocking on door hoping to get answers that will bring them peace.

In the past two years, ANPDCA has received 755 requests for information from Romanians adopted internationally and locally, plus 149 requests from biological families. The institution has eased the reconnection process through online forms and inforamtion for people looking for relatives, but underlines it doesn’t have much data for the period 1990-1994, when Romania didn’t have a monitoring system for adoptions. “The right of adopted persons to know their own roots and their own past is explicitly regulated in Romanian legislation in Law 273/2004,” ANPDCA explained in an official answer, adding that “there is no situation where the adoptee or their biological family must undergo this research process alone. All they have to do is contact ANPDCA.”

Before we rejoice at, at least statistically, we seem to be doing better and better, we have left open wounds that will continue to fester in the absence of the collective balm of apologies, recognition and reparations for the suffering – of people who grew up in the old child protection system and those who are still struggling with the emotional repercussions of international adoptions.

Simina Bădică, a communism historian, says the recent past is a subject we tend to avoid. We, our parents of grandparents, our neighbors, teachers, family friends are too many “living witnesses” of the time we institutionalized children en masse or sent them abroad. “It’s very hard to talk about such atrocities without having to take a deep breath and say: OK, but we were doing this to ourselves. Why?” Simina says in an interview for the Museum of Abandonment.

The proof that the past is still with us, even 30 years later, is in the constant search of adoptees, which in recent years comes with claims.

Marion le Roy Dagen, author of the memoir Copilul și dictatorul (The Child and the Dictator), created the community Racines & Dignité (Roots & Dignity), which represent children adopted in francophone countries. Marion was adopted in France during the communist period, when Ceaușescu personally approved around 100 international adoptions in exchange for hard currency. She was told her mother had died in an accident, but in 2000 they found each other again. Racines & Dignité call for legal investigations and official committees to look into the people who got rich from the adoption industry, apologies from the states involved, easier access to information and legal and psychological counseling for those who ant to explore their roots. Because the truth is hard to bear on your own, especially if it’s not the one you’ve been imagining obsessively.

Justice Initiative is a pan-European political initiative started in Switzerland by Guido Fluri, which seeks to restore justice and reparations for victims of child abuse in Europe. Fluri was born to an underage mother and was abusively separated from her by the Swiss state. Tens of thousands of Swiss children of single mothers, orphans, children of alcoholics, from divorced or poor families were taken by the state and placed as free work-hands for farmers and small factory owners. The phenomenon, which lasted from the 19th century through the 1980s, was called “Verdingkinder”, which means “children for hire”.

Fluri’s foundation raised 100,000 signatures for a people’s initiative that forced the Swiss Parliament to set up a solidarity fund for the victims: so far 11,000 victims have received official recognition for the harm they suffered and a solidarity contribution of CHF 25,000 each.

“We need legislative recognition of abuse, it is the only way people can verbalize the afct that an injustice has been done to them,” says Fluri. “We can’t turn back time but we can restore a bit of justice. Recognition for the harm suffered must come from the state because it was the state that caused it and it is the state that must take on that responsibility today. This small bit of justice has immeasurable power for victims of abuse. Politicians must understand the power the hold in their hands and what they can achieve by agreeing on the need to press the state to restore justice and take responsibility for its past actions.”

And it’s not just Switzerland apologizing. “The Stolen Generation” is the phenomenon of the 100,000 Aboriginal children in Australia forcibly removed from their families by the government and religious missionaries between 1910 and the 1970s. Following a national investigation, in 1998 Australia instated a National Sorry Day and continues to document and remember that past. The government of Ireland has apologized to victims of children’s homes and in 2015 set up a commission to investigate abuse and publish a report on all the irregularities. “You have been neglected, rejected and made to feel unwanted,” Michelle McIlveen, education minister of Northern Ireland, told survivors institutional abuse in children’s homes. “It was not your fault. The state has failed you.”

This autumn, United Nations experts drafted a joint statement on the traumas of international adoption: “States shall ensure that all victims, including those adopted in the past, receive the assistance they need to know their origins. For instance, States should create a DNA database that includes genetic samples for all cases of wrongful removal, enforced disappearance, or falsification of identity that have been reported, with the specific purpose of re-establishing the identity of victims of illegal intercountry adoption. Victims of illegal intercountry adoptions have the right to know the truth.”

Taking responsibility is a natural step for a dignified country, says Mariela Neagu. “Romania has a moral obligation today. Things were the way they were in the ’90s when we were an isolated and post-conflict country. It’s like holding someone locked up for years and then you let them go and expect them to act normally. But today, one of the duties Romania has is to look at its past lucidly and instate some form of restorative justice, which is so important.”

Before Romania decides whether and how it can compensate the victims of its child protection system, it must first have the strength to firmly recognize the abuse it has perpetrated – without throwing the issue to its communist past, since violations of child rights affected, as Roelie Post says, not just “Ceaușescu’s children”, but also “[Adrian] Năstase’s children and [Traian] Băsescu’s children.”

The institution that holds the historical records of adoptions is ANPDCA, a sub-division of the Ministry of Labor. For those who grew up in institutions, information is scattered throughout the archives of Child Protection Departments, which took them over from the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education, which managed orphanages before the end of communism. The entire governmental and political system was in fact involved in the issue of abandoned children.

The road to recognition and official apologies seems slow, despite the fact that the past decade has seen poetry volumes that speak about life in children’s homes, annual marches commemorating the victims of the system or efforts to memorialize and research this past, like the Museum of Abandonment. Formerly institutionalized children have bene calling for recognition since 2014, when Daniel Rucăreanu and others founded the Federeii Association, whose goal is to research their suffering and obtain their official recognition. Eight years later, Vișinel Bălan, one of the association’s co-founders and currently vice-president of ANPDCA, met with Guido Fluri for a first discussion for the support of the Justice Initiative. Recent European and international pressure could be the kick that determines the Romanian state to listen to the claims of those affected and start to acknowledge the injustices of the recent past.

It was painful to witness in real time the effects the truth had on Lucian. In the space of five months, he grieved for his mother who had died a birth, went through the hope, emotions and costs of two DNA tests, and now must make peace with the reality of a biological mother who has rare moments of lucidity. He has lived for nearly a year in Romania in an emotional roller-coaster and is now so dizzy, it’s hard to get off it.

“I am not a product. I don’t want to be a Schepers and they can’t make me. They don’t own me and I didn’t choose this life,” he told me a few days after getting the DNA result. In the absence of evidence to contest his identity, his legal battle plan no longer seems feasible.

For now, he is trying to focus on his new job in Bucharest. He works in an IT company and this time he goes to the office, which helps take his mind off the reality of his rental apartment, where he is surrounded by empty shelves and trapped into endlessly browsing his papers.

He thought that, once he knew the truth, in a few years he would get married and have children and would finally be able to start a life free from the confused story of his adoption. He still dreams he “won’t be buried with that cursed name”. As exhausting as the unknown with which he has lived all these years is, it’s still more comfortable than reality.

“I will never know the truth. Nothing will ever make sense,” he told me one day. Then he dismissed the thought because it’s scary to accept that he already knows everything there was to know. There must be some more steps he could take. He wants to go back to Belgium to confront his adoptive family one last time. “They must know more,” he told me. Perhaps his biological father’s family is less mysterious and scary than the maternal side. “There must be someone out there I will feel is a relative. Everybody needs that, right?”

S-ar putea să-ți mai placă:

Fantomele adopțiilor internaționale

Zeci de mii de copii abandonați au fost adoptați internațional între 1990 și 2004. Mulți încearcă să-și înțeleagă rădăcinile, dar căutarea poate fi copleșitoare în lipsa unui stat care să își asume eșecul protecției pe care le-o datora atunci.

Poate un copil neiubit să învețe să iubească?

Acum 30 de ani, mii de copii din România erau lipsiți de orice contact uman. Iată ce s-a întâmplat cu unul dintre ei.

Attention Deficit

Last fall, a few kids from Pitesti teamed up against a classmate they were afraid of. Nobody won, but everyone lost.