Something to Last Forever

In the Popa family, Sorin is the father, Loredana is the mother, and Huntington is the genetic disease that irreversibly changed their lives.

Note: This is the English translation of the article originally published in issue #34 of DoR magazine. You can read the Romanian version here.

For more than a year and a half now, Loredana Popa’s bedroom is in the kitchen – a small square room, with a curtain for a door, where each wall holds up a different universe. One for cooking and doing the dishes, another for eating and doing homework, another where clothes, cables and scratched CDs pile up, and the last one, next to a potted lemon tree, for sleeping and crying. Loredana is 30 and shares the pull-out sofa with a white mohair fur-ball of a cat. She is a light sleeper. This way, she hears her husband calling “Honey” in a raspy voice when he needs food, water or help going to the bathroom.

When that happens, she gets up at once. Her hair disheveled and eyes half-opened, she crosses diagonally through a hallway made even narrower by a cabinet of carefully organized lipsticks and mascaras and a shoe rack stuffed with sizes 31, 36, 37 and 44. She gets to the room near the entrance, a warm living room that now serves as a bedroom for her husband Sorin and their two children, Alex, 11, and Mihai, 5, who sleep on their own pull-out sofa. She bends over the bed to hear him better, then picks up the narrow-lidded water bottle and helps him drink as he lies on the pillow.

Hunched over, his hands crossed between his knees, the 35-year-old man lives in a bed where the disease consuming him has ample space to manifest itself: wide involuntary movements that force him into brief, awkward and fragmented interactions. He has Huntington’s chorea, a rare, incurable genetic disorder that progressively impairs cognitive abilities, physical abilities, causes emotional disorders and exposes the family to the risk of genetic transmission – both children were born with a 50% chance of developing the disease.

Starting last year, the family’s life is increasingly often dictated by immediate needs. Days begin without any formalities and “Good morning, mommy” is replaced with “Do you need to pee?” or “Do you want water?”. Next to Sorin’s bed are now objects that confine the borders of his routine: a plastic bedpan and a pack of adult diapers, of which he uses one, two and sometimes three a day. Loredana’s mornings have developed a routine of their own: she changes and cleans Sorin as the children shake off their sleep, she prepares slices of bread with an off-brand chocolate spread that the children call “Nutella”, she gets the little one ready for kindergarten, while the cornflakes for Sorin’s breakfast soften in a large bowl of yogurt.

The Popas live in the center of the small town of Mihail Kogălniceanu in Constanța county, which also hosts the city’s airport and the only NATO military base in Romania. They have been living together for 11 years in the house where Sorin grew up – a two room apartment where they only have access to the living room and the kitchen. Delu Popa, who is Sorin’s father and the owner of the place, has been keeping the bedroom locked for four years, as a spare room. From the balcony there is a view of the park, a long stretch of land with green tufts and lined with sparse trees. They used to spend four hours a day there until this summer, when Sorin became unable to keep his balance even in a wheelchair – he leans forward over his knees like a creeping vine and tumbles head first. They used to spend time there even before Sorin lost control of his body movements and his emotions, as he was employed by the town hall to maintain the lawn, the trees and the sprinklers and he knew everybody. In July, the neurologist told Loredana she had better prepare herself mentally. Her husband might have two months left to live, or a year or ten, but she needs to be ready.

Their family is one of the 50 in Romania affected by Huntington’s disease that are registered in a national record. Although Sorin was diagnosed in 2013, until this year they had not met or spoken to others like them. This September, during “Huntington Week”, an event organized by the Association for Huntington Romania at the Reference Center for Rare Diseases – NoRo in Zalău, they met 12 other families that until then had lived in isolation, affected by necessities that kept piling up under a ceiling of limited resources. However, the prevalence of the disease in Europe is of 1 in 10,000 people, which means Romania likely has around 2,000 people affected who are not recorded anywhere. People who don’t yet show symptoms, people who dismiss their muscle spasms as nervous tics, people who are misdiagnosed, people unaware of their family history. Since it is a rare disease, the patient community is small; there are even fewer experts. And when doctors only focus on their own specialty they ignore crucial signs of the disease because they have to do with psychiatry or genetics instead of neurology, which is where families most often end up. Some of them, especially those with early stage symptoms, are told they had behavioral disorders or epilepsy. With elderly patients, Huntington’s is sometimes mistaken for Parkinson’s or dementia. The wrong diagnosis comes with the wrong medication, delaying the alleviation of symptoms and making patients worse. Because it is a neurodegenerative disease, it cannot be cured.

Loredana met Sorin on May 1, 2004, in her own yard. She lived with her parents, two sisters and two brothers near the forest in Mihail Kogălniceanu. She had a difficult childhood. The building where she grew up burned down when she was little and adjusting in a new place took a while. Her parents always worked wherever they could – at an animal farm, felling trees in the forest –, so the children practically raised each other.

On that particular May 1st, Sorin had come over to take one of her brothers to a barbecue. He was 21, dark skinned and had curly hair, which is why he was nicknamed “Sheep”. In town, he had a bad boy reputation. Whenever people heard there had been a fight in the neighborhood, they immediately thought he must have had something to do with it. Sheep was fast, kicking left and right. His childhood was cut short when he was 10–11 and his mother got sick. Jerky movements had taken over her body and her unsteady gait earned her the label of “drunkard”. She later ended up in a wheelchair. Because his father had to work, Sorin took care of his mother together with Andrei, his older brother by two years.

Sorin (35) and Loredana (30) have been together for 14 years. On his 22nd birthday, Loredana’s mother had smashed his face into the cake and he did the same to her and his girlfriend. Photo from the Popa family archive.

He fell in love with Loredana at first sight, right there in the yard, and did not give up the first few times when she rebuffed his advances, he even bet his friends he would win her over. She thought he was too pushy, so she kept avoiding him for a while. It annoyed her how he often crossed her path, asking where she was going, how she was doing, if she needed any help. When Sorin started helping her father chop down and carry firewood, Loredana started seeing him every day. She realized she liked him when she caught herself glancing in the mirror before getting out of the house, when he burned her a CD with Axe Bahia’s Chuchuka, a popular song in the 2000s, when she smiled as he greeted her each morning with “Good morning, sunshine!”.

They shared their first kiss in the forest, where they were guarding the forest ranger’s calves. Sitting on a tree stump, Loredana warned him the deal would be off if he didn’t know how to kiss. So Sorin asked her how she wished to be kissed. French style, she said. Squatting in front of her, Sorin said he didn’t know how to kiss like that but he really wanted to learn. Loredana remembers the kiss lasted a few minutes. Although they never had much privacy – they lived for a while with Sorin’s brother and then his father, who berated them in the morning for “shaking the walls” while having sex –, Loredana still misses their time together as a couple: the times he hugged her tightly, the times they watched their children at play, the times they did house chores together and he would grab her ass unexpectedly. Since March 2017, they can’t even sleep in the same bed.

As she talks about it, she scrunches up her eyes as her smile draws an expression line on her cheeks. She extends her arm to show how small the tree stump where they kissed was and how he had squatted. Even though he was “a player” – he was seeing other girls and sometimes lied to her so he could have his little flings before she got pregnant –, Sorin remains the only man in her life.

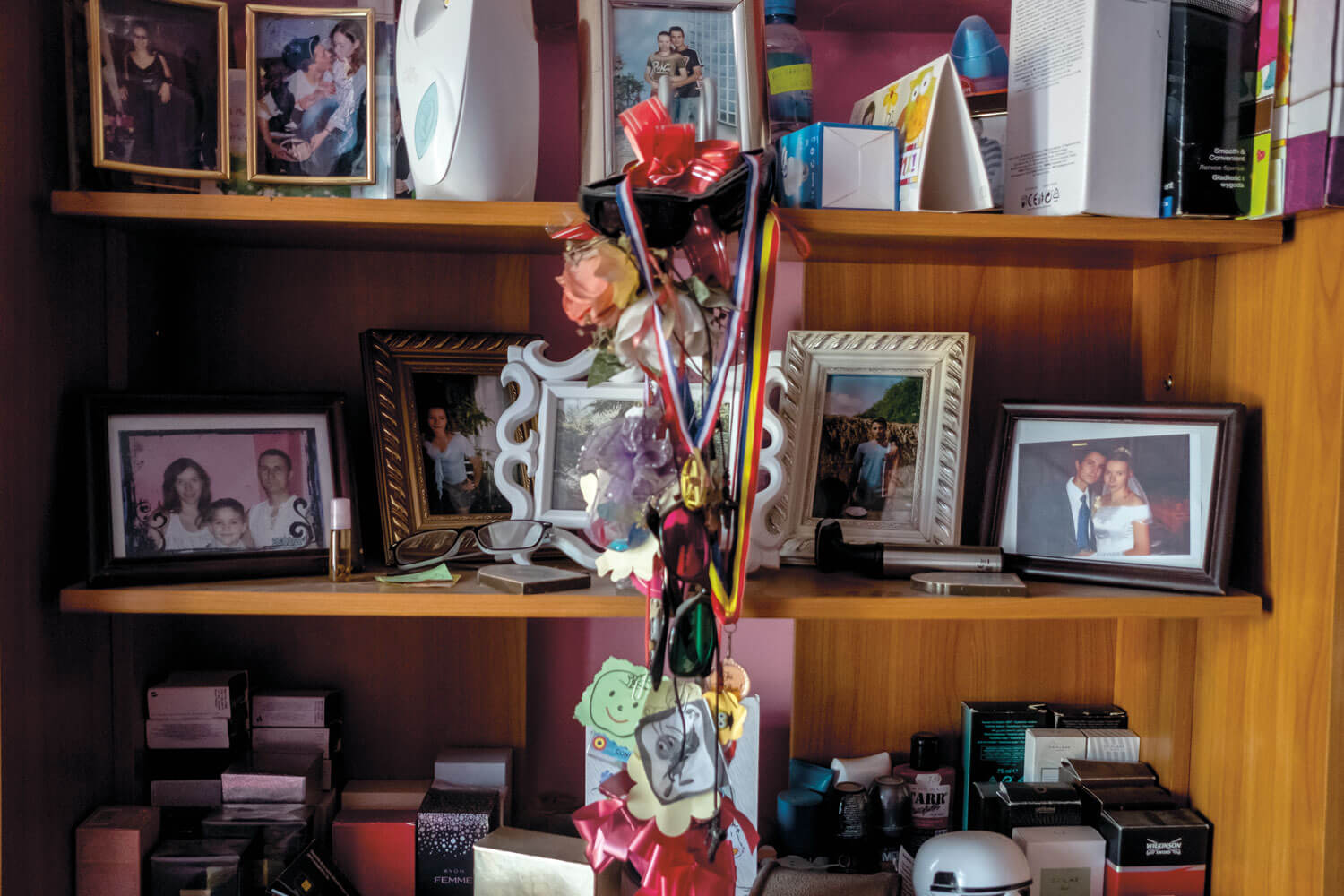

In their home, their past is displayed in 21 picture frames that widen the gap between “before and after Huntington’s”. Their first photo together is still in the glass case cabinet in the living room. She was 16 and he was 21. They were out developing photos and spotted a good picture spot in the studio, next to a festive flower arrangement. She is wearing jeans and a T-shirt and he has his hands around her midriff – slightly pulling up her shirt.

They have six photo albums in the bookcase – some printed recently, with pictures from their phones –, and Mihai, their youngest, loves to see himself in photos. “That’s me,” he says. “This is also me.” As she reminisces, Sorin fumbles in bed and struggles to sit upright to tousle Mihai’s hair. Whenever a photo of the two children comes up, he says, “They are my happiness”. “Dana, too”, as Loredana is called by her loved ones. His voice betrays the effort to speak clearly. “We loved each other very much,” he hardly continues. “We took care…” – he pauses for breath – “of each other.” He keeps bending his knees and frets about, as if pronouncing the words with his entire body.

Sorin is in many photos from the maternity ward, next to his first child. His head is on the pillow and his arms form a halo around the newborn. He had turned 24 the day before Alex was born, and welcoming a son was the best birthday present.

Because she was 19 when she got pregnant and they had their wedding one month after Alex was born, Loredana stayed with her own family throughout the pregnancy. They then moved to Sorin’s father’s apartment with their baby, whom they often left with his uncle Andrei while they were at work. Sorin had a maintenance job at the town hall for 800 lei a month and she commuted to Constanța. She made 1,000 lei a month working 12-hour shifts, seven days a week, at a butcher’s. She then had seven days off but needed two days just to pull herself back together. They didn’t have a honeymoon; they figured there would be time for that later. First they wanted to lay tiles in the bathroom and buy furniture for the bedroom, to have a “proper” home. They postponed it until they got engulfed in work, had a second child, and then the disease took over their lives.

Loredana recounts their history as she feeds Sorin mashed potato stew with bread pieces mixed in. He still eats a lot, but slowly, with a Winnie the Pooh towel for a bib. His head tilted to the side, Sorin lies down as he swallows, because the disease has pushed his chin into his chest; he cannot lean, he has no balance. This year he started to choke when eating upright. Every two bites or so, metal clangs against his teeth. Loredana asks him not to rush and, most importantly, to chew his food. She feeds him from a kneeling position or sitting on the edge of his bed and Sorin looks straight into her eyes. “You’re so beautiful”, he says lifting his hand into the air. He twiches it right to left, as if it were tied to an invisible boulder. His fingers are rigid, parted, as if intentionally tensed. He tries to caress her cheek but only manages to scratch her right beneath the eye and pull apart a strand of hair from her pony tail.

Feeding can take up to 45 minutes and it’s their time to catch up. Loredana tells him she has to go to the doctor’s to pick up her parents’ prescriptions, that Alex got a C in French, that she will go buy diapers and their neighbor Mărin will come sit with him. She always tells him where she’s going and asks if it’s OK. “Be good”, she says caressing his forehead. “You’re good anyway.” Sorin says “yes” and curls over the width of the bed, his eyes fixed on the blanket or the TV, on Kiss TV or, when the younger boy is in the room, on Minimax. He twists his hands between his knees, where their movement stops.

Loredana loves keepsakes, so they regularly print out photos. She now has 21 framed pictures – on the walls and in the glass case cabinet –, including the first photo of the two of them together, their wedding photo, as well as family portraits with Sorin in a wheelchair.

If he has eaten and taken his treatment, he doesn’t fret. Also for avoiding restlessness, he is no longer allowed regular chocolate or caffeine. His coffee substitute is now a mug of white chocolate that he drinks through a pink straw that Loredana washes and reuses every morning. After lunch, she checks the treatment plan and Mihai offers to feed his father his pill. He holds the pill with three fingers and carefully places it onto Sorin’s lips: “Here you go, daddy.”

Sorin has always had an unsteady gait, but blamed it on football injuries. Loredana became worried when he started dropping things, falling over and could not reach his own mouth anymore when eating his soup. Five years ago, when they christened Mihai, he was already showing symptoms. His hands swayed independently. He had lost weight and his face looked hollowed out. He would lean on one leg and then the other but refused to see a doctor.

One day, they were home and Loredana had just breastfed Mihai. Sorin picked him up and was walking with him through the apartment to keep him awake. He stopped by the kitchen, where Loredana was doing chores, and took him to the bedroom. Suddenly, she heard a thump and then Mihai crying. She found Sorin on his knees, on the carpet, panicked that he may have hurt the child he was still holding. “You take him”, he said to her, mortified, and since then only picked the child up in bed.

Whenever he lost his balance and his knees weakened and his hands jerked away from his body as if at the push of a button, Sorin’s father said he had “his mother’s disease”. But he didn’t know the name of it, nor could he show any medical records with a diagnosis to Loredana, who had never met her mother-in-law. Sorin always thought his mother had died of multiple sclerosis and that she had had some other illness – the name of which he didn’t know, just as he had no idea that he and his brother could develop it. Sorin understood he inherited Huntington’s from his mother’s side, a disease he now deems “perverse”. He didn’t have the time to develop a relationship with his mother, as he was more of a caregiver than a son to her. He and his brother would take her to the park, to barbecues with the neighbors, feed her and give her her treatment, bathe and change her. The hardest part was when she was on her period.

His mother’s death was followed by that of Andrei, Sorin’s brother. At 29, he went missing and was found dehydrated and sunburned on a dirt road near the city of Constanța. He had always been scrawny and kept to himself but no one knows whether this had anything to do with his mother’s illness. Loredana and Sorin missed him dearly. He took care of Alex and he was also the brother, brother-in-law and friend with whom they spent evenings watching wrestling and football, with seeds and Cola on the table. After he died, his father sometimes stayed in his room, coming and going from his girlfriend’s, but since 2014 the room has stayed locked. Since then, although Alex sometimes asks when he could have his own space, Loredana, Sorin and their boys only use one room.

For families, Huntington’s is a disease that brings them together but also a secret that tears them apart. Many don’t know they are at risk and find out details after getting diagnosed, by digging up memories they can no longer verify. If the disorder manifests itself late in life, its symptoms are often disregarded among regular signs of aging. Most people are married and have children by then and the diagnosis of this genetic disorder hits hard. Others hide it from their families out of shame and helplessness – they don’t want to be pitied for dying.

It’s been nearly a century and a half since the American doctor George Huntington thoroughly described the disease that now bears his name and 25 years since a team of researchers identified the responsible gene. Because stigma has kept patients out of the public eye for a long time, research has always been difficult and without much hope for generations already exhibiting symptoms.

Each part of our body is determined by the DNA we inherit from our parents – a molecule like a never-ending coiled ladder that stocks genetic information on vulnerabilities, illnesses, life expectancy. The gene that will kill Sorin is called HTT and is located on the short arm of chromosome 4. We all have it. The difference is that the gene is much longer in people with Huntington’s. The trio cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) repeats itself on it, like an inexplicable genetic stutter. When the sequence is repeated more than 35 times, it produces abnormal quantities of Huntingtin, a protein that becomes toxic and progressively kills brain cells, turning the brain into mush. The bigger the CAG repeat count, the sooner symptoms are exhibited and the disease progresses as if it were skipping steps.

In terms of challenges and suffering, experts agree Huntington is one of the most wretched disorders. A curse, say family members. It’s not caused by a virus nor is it sexually transmitted but it’s genetic, inherited from one’s parents. It doesn’t just affect the mind or the body, but both. It doesn’t just mess up relationships at work or relationships with loved ones, but all the relationships of a person. The circle is completed by the reality that one cannot be cured of Huntington’s.

After he started showing symptoms, Loredana barely persuaded Sorin to go to the County Emergency Hospital in Constanța. He was held there for six days for testing and, in the end, neurologist Any Axelerad Docu diagnosed him on October 8, 2013: Huntington’s chorea and mixed anxiety and depressive disorder. Docu says Sorin’s disease was already in a medium stage: “Body movements were ample, sudden, accompanied by restlessness, his gait was already unstable.” Although the clinical symptoms were telling, the diagnosis was not validated by a genetic test. In Romania, because Huntington’s is not yet included on the list of chronic disorders, genetic testing and medication are not covered, nor are there any specialized centers. Loredana didn’t have 250 euros, the lowest price she could find at a genetic testing lab. She didn’t have that kind of money later on either. In a family with two children, 250 euros to confirm a diagnosis she saw reconfirmed every day was simply not an option.

Sorin was tested this fall during “Huntington Week” and at the end of November he learned he has 52 CAG repeats. Considering the early age of onset, the number is not surprising and explains the rapid progression of his illness. International statistics show people with 50 repeats exhibit the first symptoms between the ages of 24 and 30. If the repeat count is over 60, it’s juvenile Huntington’s, and the disease will be triggered before the age of 25.

Although she had learned to pronounce the name of the disease that had changed their lives, Loredana didn’t grasp its impact from the beginning. Disparate pieces of information huddled inside her head and explanations exhausted her. She told some people Sorin walked unsteadily due to a football knee cap injury, she told others he was affected by the cold water from fixing sprinklers. She knew Sorin would lose control over his own body, that his thinking would be impaired and their own children were at risk but the present made that horde of troubles seem distant.

At first, a person with Huntington’s loses balance and short term memory, becomes highly irritable and their movements become increasingly uncoordinated. Gradually, movements become violent and are accompanied by behavioral changes – sometimes manic, compulsive –, and patients start having difficulty speaking. As the disease progresses, writhing motions settle down. They are replaced by rigidity, a muscle tenseness that sometimes affects ability to swallow and may lead to suffocation. At the last stage, cognitive decline sets in – patients no longer recognize their family and lose their memories. Most often, the heart has the last say, at approximately 15 years after the first signs. But the progression of the disorder varies significantly between individuals. Sorin’s decline quickly burned through several stages and his progression is not standard. In just five years, Sorin went through major behavioral changes – heightened egocentrism, aggressiveness, suicide attempts –, and rigidity is starting to replace his uncontrollable movements.

When involuntary movements took over, a simple shower became a dangerous feat. Nearly a year after he was diagnosed, Sorin was still on his own two feet and he and Loredana still took baths together. They were both naked when Alex announced from the hallway he needed the toilet and his mother rushed to lock the door so he wouldn’t see them naked. “Don’t turn the water on”, she said to Sorin, who had turned on the tap before she even finished her sentence. He slipped backwards in the bathtub and fell outside of it, onto the toilet bowl, which he smashed with the weight of his body. When he fell, a rib punctured his kidney and another broke. He spent seven days in the hospital.

Soon, aggressive episodes replaced all forms of affection. Loredana calls them “fits”. When she wouldn’t let him out of the house – this occurred randomly, day or night –, Sorin would shove her between the door and the wall, grab her by the throat with one hand and punch her in the chest with the other. “I put my hands up like in boxing and waited for him to stop”, she says. This had never happened between them before. Loredana told herself Sorin was consumed by anger and helplessness and was taking it out on her, blaming her for making him go to the hospital where he was diagnosed.

Starting last year, Loredana is a personal caregiver for Sorin and her day is divided between his needs and those of the children. Still, she always finds five minutes to pencil her eyebrows, put on lipstick, put on her rings and look the way she did when Sorin met her.

Once, in a fit of rage, Sorin ripped the curtain off its rod to get to the balcony. He pushed the clothes lines with his feet, climbed over the edge of the balcony and remained dangling on the outside, a few meters above the ground, his palms rigidly clutching the rail. Loredana doesn’t know where she gathered the strength to pull him back in. She grabbed him by his underwear – the only thing he was wearing – and propped her feet onto the inside balcony wall. Suddenly, Sorin started helping, as if awoken from a bout of sleepwalking. He pushed his legs onto the building’s facade and came up grazed, scratched and out of breath from the effort. It wasn’t the only time he tried that and twice Loredana pulled him back with the help of their elder son.

“I wanted to die”, says Sorin. “It wasn’t me, it was the disease.” He doesn’t have the strength to do this anymore. The last time he attempted, he collapsed on the carpet before reaching the balcony door.

Sorin’s attempts are not uncommon. When they come to realize what their lives would be like in the next years, some Huntington’s patients make the one final decision they can still fully control – commit suicide while they are still clearheaded.

The children have always witnessed these “fits”. At just six and a half years old, the older child knew he had to hide the kitchen knives when “daddy got mad”. Sorin threatened to cut himself if Loredana refused to unlock the door for him to leave. Although he didn’t cut deep, he did scratch himself and the child saw everything. Sometimes, he would try to defend his mother. “When Sorin grabbed me by the throat once, Alex jumped onto his back”, Loredana says. On that occasion, Sorin slammed his son against the wall, with an oblivion and strength he could not control.

In 2015, Sorin was able to get a wheelchair through the Health Insurance House. Although he could still walk out of the house, the wheelchair went with them everywhere. After descending one floor, his legs weakened by the time they got to the park entrance, just 100 meters from their building. Then he would grab on to Loredana’s neck and she would wrap herself around his arm. Oftentimes, they would leave the wheelchair next to a park bench and she would dare him to walk – like teaching a small child how to walk. She would walk in front of him, her hands outstretched so he could grab on if he felt faint, and would slide under his arm when she saw his legs weaken. For their close friends, seeing him in a wheelchair was not so much a surprise as it was a relief.

Loredana knew she had accepted what was to come when seeing him in a wheelchair no longer knocked the wind out of her. Until then, people’s gazes followed her for a long time after she said hello. Some of them let slip mean comments: “Why doesn’t he push the wheels himself?”. People with Huntington’s don’t have a good grasp of distances and Sorin couldn’t maintain a course – he swerved involuntarily, was unable to coordinate his hands and sometimes flipped over.

Oftentimes, Loredana would take Sorin to the park with the children and people would gather around them when they laughed. Mădălina, her best friend, would join them, and the guys in their building would joke, “Sorin, you have two women now?”. “His girlfriend and his wife”, came the answer with a smirk. They would laugh at everything and Loredana was often judged for it. “Some people criticized me for laughing too much. What do I have to laugh about when my husband is sick?” They also had trouble with their downstairs neighbors, a couple in their late 50s, who complained about stomping noises they heard day and night.

They didn’t understand that Sorin banged his feet on the floor because he couldn’t control it. He still hits the bed-board at night with his legs and when he falls it’s five times harder to get back up – it’s also much louder.

Attempts to regain control over his own body landed Sorin in the hospital back in 2016, with a head injury, and twice again this year. Once, before Easter, when he tried to go to the bathroom alone and fell, hitting his head on the baseboard in the hallway, and then in September, when Loredana was learning about the rights and obligations of people with disabilities at the NoRo Center. Sorin was in his wheelchair when an involuntary movement made him hit his head on the wall. An ambulance drove him to the hospital. An hour later, Loredana came back laughing. “He got a tattoo. He’s stitched up all nice”, she joked to people who were concerned.

Three years after getting a wheelchair, Sorin can no longer use it. This year Loredana felt she could no longer carry him down the stairs by herself, “it takes a man”, so outings in the park during summer are fewer. From four hours a day, they’ve been to the park five to ten times the entire season. The last time they went out was back in August, when her brother came from Italy. Marius is an old friend of Sorin’s, they used to barbecue in the forest together and he hadn’t seen him in six years. The change hit him hard. “We used to chop firewood together, now I have to carry him”, says Marius.

Marius insisted they all go to a nearby restaurant. He carried Sorin from his bed, down the stairs and outside the building, then pushed his wheelchair down the street. At the restaurant, he ordered a non-alcoholic beer for Sorin and Loredana cut his pizza into small bite-size pieces. It bothers Marius that although part of their old gang is still in town, none of them ever visits Sorin.

At the most recent neurological examination – he is taken for a check-up every six months –, Sorin couldn’t make it on his own two feet and the doctor came out to the car. “The disease is now advanced”, she told them. Involuntary movements are scarce and his body is rigid. He no longer speaks in sentences but a few key words uttered with heavy breath broken by coughing fits. He is bound to lose his ability to speak, his body will become immobile and his cognitive abilities and memory will also be lost. Loredana is grateful that the doctor told her this point-blank, with Sorin next to her, without giving them false hope. She cried in silence for about three nights, then started over.

Twenty-five years after the gene causing Huntington’s was identified, clinical studies aim to prevent excess Huntingtin secretion even before the first symptoms. The third stage of an international study led by pharmaceutical company Roche, testing the most daring strategy so far, is set to start in 2019. The gene silencing technique seeks to stop the disease from progressing by administering monthly lumbar punctures. Most subjects are aware that they will not benefit from further discoveries but future generations might. Right now, experts say clinical studies don’t guarantee an alleviation of symptoms for patients in advanced stages nor do they lack side effects.

In Romania, such studies are science fiction. Because there are no clinics specializing in Huntington’s in the country, no Romanian may be accepted in a clinical trial despite meeting all requirements. The community of Romanian patients is still invisible although this year a major step was taken at the NoRo Center, where 13 affected families got together. (Loredana called it the “Huntington honeymoon”, as their trip to Cluj was also the first time they flew on a plane.)

Ramona Moldovan, the only genetic counselor in Romania certified at a European level and the one who organized and funded the camp, together with a team of Romanian and international experts, has been trying to get them together since 2009. She started out with five families in 2011 and now has around 50 families on record. Together with a team consisting of neurologist Vasile Țibre, geneticist Radu Popp and psychiatrist Cătălina Crișan, she examines, treats and assists patients and people at risk for free, at a center that runs with the collaboration of the Babeș-Bolyai University of Medicine and Pharmacy. The Association for Huntington Romania is an umbrella-name and a Facebook page that helps them reach more affected people, whom they put in touch with one another to help reduce the isolation and stigma. Moldovan is a firm believer in efforts made from the ground up, from families to public policies and draft legislation, because it is affected families that have the motivation and credibility to exact change. One such change would be including Tetrabenazine (under the names Artesyd or Tetmodis) – a drug that costs more than 500 lei a month – on the list of reimbursed medicines.

It costs a lot to treat an incurable genetic disorder, to adjust your life and habits, to round the edges of your furniture for when you’re no longer able to judge distances, but the costs of Huntington’s are not just financial. Those affected are born with a predetermined route but the implications of the diagnosis affect the entire family, as siblings, parents or spouses become caregivers or, as they are referred to in the literature, the “forgotten ones”. Some look at the person next to them and realize they will not grow old together. Others seek isolation and blame themselves. Huntington’s disease is a boot stomping on the mind, on resources, on what’s left of a person’s humanity.

At 1.67 meters and 53 kilos, Loredana is like a speed train carrying bills and pension coupons in her wallet, where she always has a pen, she runs around to get prescriptions at the beginning and end of each month, orders medication, visits her friend at the store and greets at least three neighbors on the way. Some of them ask how Sorin is doing. Because she turned 30 at the beginning of this year, she wanted to do something “crazy”. She had the number 88 inside a heart tattooed on her left wrist, with an A for Alexandru to the left and an M for Mihai to the right. 88 is the number both children had at birth, she was born in 1988, her parents live at number 8, Mihai was born on the 16th, “which is 8 plus 8,” she got her driver’s license on March 8. When she got to the tattoo parlor and saw they also did piercings, she decided to double the “crazy”: she got her bellybutton pierced.

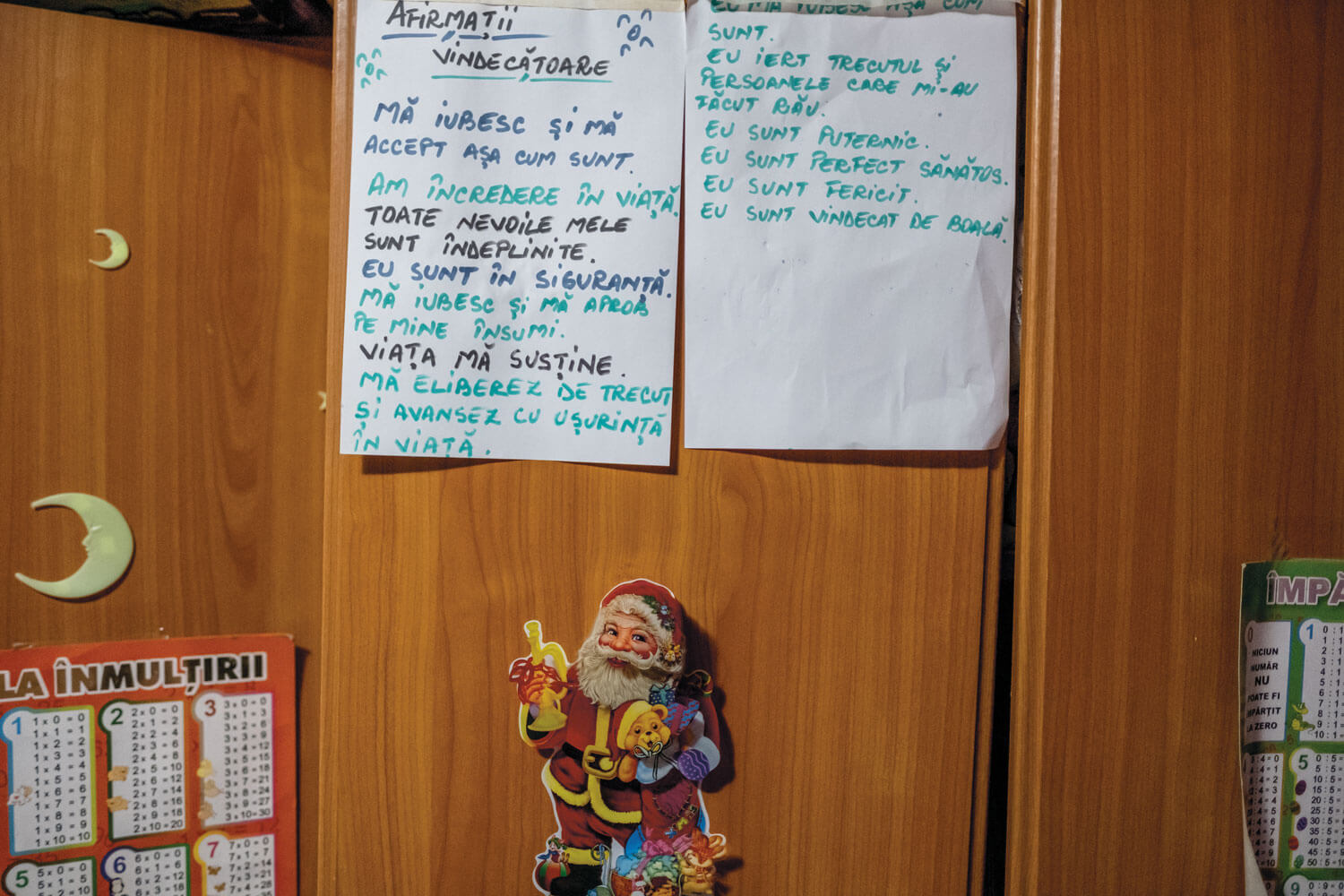

Three years after Sorin was diagnosed with Huntington’s chorea, Loredana sought her motivation writing down positive verses in a notebook. She and him repeated those mantras every morning and she later wrote them on two sheets of paper that they see every day.

Loredana doesn’t know what mindfulness is but she practices it every day. She calls it positive thinking and she found it again in the prayers she wrote in a notebook two years ago, when she asked Sorin to repeat after her: “I am strong”, “I am perfectly healthy”, “I have confidence in life”. She filled two sheets of paper with these motivational verses and taped them to the wardrobe, between two posters of multiplication and division tables. “Healing affirmations” reads the title written in black felt tip pen. She may not go to church every Sunday but Loredana believes in God and His miracles. “When someone helps you out of the blue when you need it, those are miracles too.” Like the call she got from a woman in the neighboring village offering her a cleaning job. She needed the money and now she would get 150 lei for a day’s work. “That covers Sorin’s diapers or pays a bill”, she says. Sometimes she cleans for the same client twice a month, other times her services aren’t required for three months.

She can’t afford to be depressed thinking about the future so she chooses to laugh and disperse her contagious energy as if from a magic wand. Not even after two or three errands in town, cooking and feeding her husband and children three times a day does she feel tired. And as long as Maluma is playing in her headphones, she can walk an extra mile.

Starting last year, Loredana is a personal caregiver for Sorin. She still puts on makeup every morning, puts on her bracelets, her rings, pencils her eyebrows. Some people ask her where she gets the time to do everything but what they really mean is “why bother?”. Others drop rude hints when they see her all dolled up and she always answers, “This is how Sorin met me and wants me… like in the early days”. She can’t tell what she got used to first, Sorin’s illness or people’s mean remarks.

Last year she found she has heart problems, just like her mother. A twisted artery puts her at risk of a heart attack and sometimes she feels out of breath. “That’s why I prefer to stay calm and not take things to heart.” She took the prescribed medication for three months and then stopped. It made her drowsy and she felt she couldn’t keep up with her life in that state. She has no plans to go back for a check-up – she has no time to waste seeing doctors for herself.

She knows a more advanced stage of Sorin’s illness means he won’t even be able to turn over in bed and she doesn’t even dare think about a palliative care center – there’s no way she can afford that. Sorin’s mother was at home until the very end. Although a center opened this summer in Cumpăna, a town in the county, its contract with the Health Insurance House only covers 20 days a month. After that, patients may be moved to the center’s private area, which has 25 beds for a fee, or they can go home and return the next month. More than anything, Loredana hopes her own body won’t fail her – she prays to God to keep her in good health so she can continue to help Sorin.

Her second tattoo, which she got this year before his 35th birthday, is also about hope. “For you, something permanent”, she told him when she showed him the Huntington’s symbol – the blue ribbon – within a butterfly whose body is the word hope. “A butterfly only lives for one day”, she says “but dies hoping it will live another day.”

Although she writes down a shopping list at home, Loredana often forgets to take it along and ends up going back to the store or improvising as she goes, within the means of her budget. She goes shopping in Constanța once or twice a month at most and that means she will be away from home for three hours. She shops at Lidl, Kaufland or Carrefour and sometimes she takes her mother along.

From Lidl she gets chocolate spread, cereal with honey and cornflakes for Sorin, chocolate-coated cereal for the children, meat, sanitary pads, a jar of pickled cucumbers that she picks up, puts back on the shelf and picks up again, because it costs 6 lei and the pickles are thin. She was going to get minced meat for a meatball soup but she sees packs of chicken drumsticks at 5 lei for five pieces. She takes two packs and decides to make a stew and a chicken soup. Nearly all the products in her cart are discounted or on offer and she pays 45.80 lei at check-out.

In the next hypermarket, they both start comparing prices. “Bananas are 3.49 here, at Lidl I paid 3.99, too much,” says her mother. She gets tomato sauce for 4-something lei and checks the price two or three times. “Tomatino, 4 lei, it’s OK.” She grabs two bottles and flips them upside down to see how thick the sauce is. She gets in line for olives – green olives are one of her few indulgences and she buys just 100 grams of three kinds of olives. It comes in at under 15 lei. She buys a two-kilo jug of yogurt for 6 lei and says it lasts four or sometimes five days. After she puts the Kaufland-brand milk in her cart, a bucket of sour cream and four packs of baby wet wipes for Sorin, she can think about luxuries: a bottle of Adria peach-flavored juice, a cheap brand of juice, two bags of mini croissants with champagne-flavored filling, Sorin’s favorites, two bags of potato chips for the children and two bottles of aloe vera juice for herself and her mother. On the way to check-out, she adds everything up in her head, “so I don’t make a fool of myself”. At Kaufland she ends up spending 116 lei.

The cereal bag advertises a competition where you could win a vacation home and that amuses her. If she had more money she would buy a car, to do all her errands faster, then she would buy apartments for her children “so I know they’re all set”, then she would take Sorin to see the world. Loredana got her driver’s license last year and bought a used 2001 Alfa Romeo from the mother of a friend in the neighborhood, who sold it to her for 800 euros, which she borrowed from her parents and her neighbor Mărin. She still owes him 900 lei. In less than a year, the car broke down and now sits in her parents’ yard.

Sorin takes three pills in the morning, one at noon and five in the evening. He takes medication that helps reduce sudden involuntary movements caused by the chorea, but also antipsychotics to prevent depressive and manic episodes.

Because genetic testing and medication are not reimbursed, patients also lose their dignity when it comes to money, which is never enough. As a personal caregiver, Loredana gets 1,287 lei and his illness and disability pensions add up to 1,220 lei. The children’s state allowances add up to 168 lei. Although Loredana sometimes cleans people’s homes and sometimes sells Avon cosmetics, this extra income is not regular. The nearly 2,700 lei a month must sustain four people – an ill man whose treatment, excluding diapers and other hygiene products, costs 550 lei a month, two children who go to school and kindergarten, respectively, and a woman working hard to make ends meet. Utilities and other bills are nearly 300 lei when it’s warm outside and they don’t have to pay for gas, which in winter can cost as much as 400 lei.

When she doesn’t have the money to pay on time, she borrows from Mărin, a main supporter and a “spiritual father” for Loredana. He is 60, has almond-shaped eyes and salt-and-pepper hair and his is one of the names Mihai says when asked “Whom do you love?”. He lives in the next building and has been close to them ever since they moved in. He liked them from the start because “you could see they loved each other” and he’s known Sorin since he was a boy. Before he became ill, he used to take him along to chop wood and could always rely on him when he had work to do. He knew his mother and is friends with his father but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t criticize him. “He works at the town hall, he cuts trees in the park, but he never comes to see Sorin.” And when he does visit, he asks if he’s eaten and then quickly leaves. “I told him to ask him how he’s feeling, to stay a while, not like this.” When Loredana couldn’t take Sorin to the park, Mărin stepped in. He thinks it’s only natural he should stand by them now, when they need help, even though that gets people gossiping. “People think I’m sleeping with Dana,” he says. “Had I been 40–45, I would’ve understood but I’m 60!” He chides her sometimes when he sees her pressing her hand against her liver. “If she gets sick, you’re doomed”, he tells Sorin when he gets restless. Then he encourages her, hugs her and sends her to the doctor. “I’ll watch the children, just go.”

Loredana’s parents live on the edge of town, half a kilometer away from the main road, and it’s nearly an hour walk. They are 55 and 58, respectively, her mother has heart problems and her father has asthma but they still work – she works shifts at a soda factory and he works at an animal farm. They both make minimum wage. Although they don’t visit very often either, her mother sometimes rebuffs her for going to her best friend Mădălina to talk instead of coming to her. Loredana doesn’t contradict her but doesn’t feel she could do it differently. Whenever she asked for help, her mother barely had time for her chores. Besides, she knows it would be a long walk for her, while Mădălina lives nearby and they’ve been friends since ninth grade.

When needed, Mădălina comes over to watch the children. Meanwhile, she has learned to feed Sorin and this year she changed his diaper. “Put him in the bathtub, that’s what mommy does,” said Alex, who already knew the drill. But Mădălina was afraid he could slip and hurt himself. She filled a basin with water and asked Sorin to bend over the side of the tub, she cleaned him with a sponge, then wiped him with wet wipes and put on a new diaper. It was hard for her, him being a man, but she had done this before for her aunt who was bedridden after an accident. And when she realizes what the children see every day, she no longer thinks about her own embarrassment but how to be there for them.

Because he is at kindergarten just four hours a day, Mihai is mostly at home. When he’s not poking an inquisitive finger into whatever his mother is cooking, he plays Minecraft Skywars on the phone or asks Sorin to let him watch cartoons. When he gets bored, he hovers around the side of the bed and tickles his father so he’ll be tickled back. He stands next to his father and moves his little fingers on his abdomen, which flinches up and down. Struggling to synchronize his fingers on Mihai’s “funny bone”, as the boy calls his ribs, Sorin wants to pull him closer to his chest but involuntary thrashes send the child into the bed board or to the side of the bed, bare feet up. Mihai has learned how to throw himself so it doesn’t hurt. He lifts an index finger and says, dimples in his cheeks, “I’m OK!”. Sometimes Sorin scratches his neck because he can’t control his movements even when he wants to hug his child.

Before he completely lost control over his own body, Sorin and Loredana used to take baths together. With two children in a home with just one room and a kitchen, bathing was their moment of intimacy.

What Mihai knows about his father’s illness is that he can’t have chocolate because it makes him restless. That he can’t get out of bed unless “he holds on to mommy”, that he fell twice and went to the hospital. He also knows he likes tea, eggs, cheese pie and beans. They play “catch” together although Sorin can’t catch the ball, but pushes it back with the back of his hand. He remembers how his father used to push him in a swing and waited for him to come down the playground slide.

“What was daddy like when he took you to the park?” Loredana asks him.

“He was young”, says Mihai.

Alex has more memories with his healthy father. Sorin used to pick him up from kindergarten, bought him Măgura cake and Tedi fruit juice and let him play Counter Strike on the same computer on which, later on, Loredana searched “what is Huntington’s disease”. He’s never heard of the disease his father has but remembers the first explanation his mother gave him. “He stood in cold water when fixing sprinklers in the park and it damaged his bones.” He knows the disease set in after his brother was born and progressed with time. Loredana scolds him when he says “maybe if Mihai weren’t born, daddy wouldn’t be sick” in an attempt to piece together what little he knows. He doesn’t know exactly what causes the disease – “from what I know, his dad had it and gave it to his mom and she gave it to my dad” –, but he knows how it all ends: “In death”. He doesn’t know he could develop it as well.

Alex says he hasn’t had time to read the leaflets on Huntington’s his mother brought him – which would have explained to him the involuntary movements, the fits of rage and the fact that the disease is hereditary –, but Loredana is at peace. The boy goes to see the school counselor when he feels the need to and she encouraged him to do so from the beginning. “I tried to explain to him that it’s nothing to be ashamed about, on the contrary”, she says. “It’s perfectly normal for him not to talk to me about everything but he can go there and let it out.” Loredana took some leaflets to the boy’s class teacher and asked her to tell her if she notices anything wrong. She figured she would be close to him for the next four years and she would notice any changes – emotional, in focus, in behavior. Loredana believes one’s mental state matters a lot in the onset of the illness.

However much she wishes the boys inherited her genetic baggage and not Sorin’s, Loredana knows she will have to get them tested. But she doesn’t want to ruin their childhood and the doctor who diagnosed Sorin recommended that she wait – if there are no worrying signs – until they turn 18 and can decide themselves whether they want to know.

Before he completely lost control over his own body, Sorin and Loredana used to take baths together. With two children in a home with just one room and a kitchen, bathing was their moment of intimacy.

In 2018, nearly anyone can pay between 400 and 1,400 lei – depending on the testing technique – for a genetic test that only requires a regular blood sample. The DNA is currently examined only in labs abroad. Ideally, people should talk to a genetic counselor before deciding whether they want to get tested, says counselor Ramona Moldovan. In the UK, for instance, a person cannot be tested if they’re not showing any symptoms without at least three counseling sessions. In Romania, however, genetic counseling still rings exotic – it’s not even included in the denominator –, and is associated with cherry-picking genes for a future child, not with family history. Moldovan thinks anyone should know all the implications of a decision and these can be thoroughly examined during counseling session, which could prevent tragedies. There are people who get out of context information on Google, get tested at a private clinic, they receive their CAG repeat count in an e-mail and learn they have 10 to 20 years to live in horrible conditions, with a degrading end and a heavy genetic baggage they’re leaving behind. Because of the shock, some commit suicide. “A large part of the blame belongs to private clinics”, says Moldovan, because they send people the repeat count and close the door just when it should be left open for discussion and support.

Although they know they are at risk, some people choose not to get tested because they don’t want this hanging over them. They don’t want to be haunted by the thought that they dropped a mug because they are tired or they dropped it because they have Huntington’s. On the other hand, others need to know because, depending on the result, they choose to stop postponing experiences, to live more in the moment or to become a spokesperson for the rights of people in the community.

Loredana doesn’t ignore the thought that either or even both her children could inherit Sorin’s disease. But, just as she is there for their father, she says she will be there for them, no matter what. She lives in the present like a mantra but says she has thought about her sons’ future relationships. “I’ll be careful to make those girls aware of what they might be getting into”. If neither of the children has inherited the gene, Huntington’s disease within the Popa family ends with Sorin.

Since she accepted the disease, Loredana started looking at things rationally. “If I think about what Sorin used to be like, that won’t bring him back”, she says calmly, looking down. “We’re moving forward and I have to move forward.” She clings to positive signs and is happy when the coffee foam takes the shape of a heart or when she finds a hair wrinkled in the form of a heart on her clothes.

“Someone up there loves us and this is what we must give in return.”

Out of a maximum score of 100 points, Sorin scored 5 at the latest Barthel test, which measures a person’s independence in their everyday lives. Starting this year, he is fully dependent on his family for his daily needs.

On Wednesdays and Saturdays it’s bath time for the entire family. For Loredana, the hardest part is when it’s Sorin’s turn. He lost over 20 kilos in the past five years and his spine protrudes through his sweatshirts, but he is harder and harder to move since he can’t pull his own legs. When she gets him ready, Loredana lifts his shirt up to his chest, takes it off over the head with swift, calculated maneuvers that leave no room for questions. She pulls his sweatpants down from the ankle, together with his socks that fit tightly on his toes and heels. She bends towards him and asks him to put his arms around her neck and Sorin balances his torso trying to lift himself. Loredana lifts him by the midriff and finds his center of balance.

Once she gets him in the tub, she needs to move fast – before he tries to get up and slip and hit himself on the tiles. She lathers him with soap, rinses and shaves him, then gets him out of the tub in a “three-step turn”: first she lifts his knees over the bathtub, then wraps his hands around her neck and asks him to push himself up while holding tight onto her neck. “It’s getting more and more difficult,” she says. “Sometimes we both fall.” She wraps him in a large absorbent towel and they limp together a few more steps to the bedroom. Sometimes Alex meets them at the door and holds his father with one arm. It’s mental support for his mother, who is struggling not to drop him. When they lay him on the bed, Sorin is drowsy from the steam. After his bath, his arms are too limp for him to touch Loredana’s cheek. She places his arms around his body and pulls the blanket underneath his chin, which rests on his chest.

It’s not even nine but it’s been dark outside for a long time. The children get on their own sofa and Sorin’s eyes remain staring at the ceiling for a few seconds. He sees the styrofoam heart he made himself eight years ago. He had a sheet of styrofoam left and thought he would surprise Loredana, who was working shifts at the butcher’s and came home late at night, dog tired. He cut out and painted red a heart bigger than a light fixture. When she saw it, Loredana was speechless. She called it “eternal love on the ceiling” and every time they painted since then, they looked for a color to match the heart.“Because we’re never taking it down”, Loredana says.

Acest articol apare și în:

S-ar putea să-ți mai placă:

Pentru viață, tot înainte

În fața războiului, un cuplu se mută din Kyiv într‐o fermă din Portugalia. Cum arată o astfel de călătorie când realitatea e un cumul de contradicții? Și cum privești în urmă, când familiile te îndeamnă să privești tot înainte?

Who Am I in the World?

Until I was 25 years old, I was convinced that I’m just a label of my ethnicity and that my world was predestined to remain between 4 walls of dirty glass. Then I left.

Apicultura la pensie: din mijlocul stupilor direct pe YouTube

Ion Stănescu are 73 de ani și s-a apucat de albinărit la pensie, când și-a dat seama că munca pe lângă albine îl ajută să-și păstreze mintea vioaie.